THE BURNING OF ELMIRA - Treachery, Murder And Miracle In Braxton County

The tortuous and miraculous story, "The Burning of Elmira" by R. N. Nicholas, courtesy of Orla Siers, is published on the Hur Herald for the first time in this article.

George Hall points to the site of the Issac "Ike" Siers

house, the family spared death by intervention of a child,

house burned to ground, nearby in woods is family cemetery

By Bob Weaver 2019

The burning of the Braxton County village of Elmira is often recalled by the families that had roots in the community.

George Hall, son of the late teacher Ray Hall, still lives in the long-gone village with his brothers, recalls the incident that caused Union troops to descend on Elmira families with the intent to kill and destroy.

"They came from Summersville to kill Issac "Ike" Siers and his family, after a relative told Union troops he was a Confederate sympathizer," said Hall.

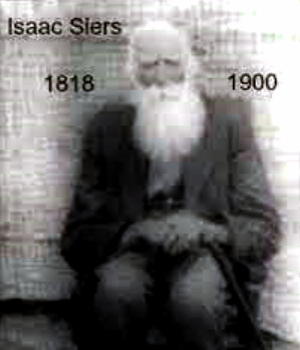

Soldiers came to kill Issac "Ike"

Siers (1818-1900) at Elmira ...

... but he and his family was spared with

the intervention of his daughter 4-year-old

Paulina "Pliny" Sears Vaughan (1861-1940)

Siers had apparently sold some horses to a group of Confederate sympathizers.

Arriving in the village, the Union troops burned, plundered and pillaged the residents, but most of their threats were against the Siers family.

Most accounts say that Siers would have died if it were not for his four-year-old daughter Pauline "Pliny" Isabel Siers, who went face to face with the head officer, clinging to him and asking for mercy. The plea was successful, but his home was burned.

The sparing of life was in direct conflict with military orders.

"Pliny" latter met and married Ben Vaughan. Many of the men in the Vaughan clan were postal workers and mail carriers over four generations, including Calhoun resident Bert Vaughan whose life and times were recorded by National Geographic in 1954.

According to Land Grant records, in the 1850's, Isaac Siers received about 150 acres in Braxton County from two grants. The first in 1850 was a parcel of 70 acres. The second, a few years later in 1853 was 80 acres.

Elmira residents recall treacherous Civil War story (L

to R) George Hall, Helen Vaughan Cobb, Hope Vaughan

Ninety-one-year-old Helen Vaughan Cobb, who still lives in the village, recalled the incident involving her great-grandmother Pliny. "It was a treacherous time with life in short order, and the consequences were devastating," said Cobb. "There took everything of value, burned their home and spared their lives."

Hope Vaughan, who lives in the village, said her husband, Larry Vaughan, followed the family tradition as a mail carrier. She said most of her family have been grateful people "clinging to the Lord."

George Hall said the Siers homestead is on his property and many of the clan are buried in a primitive cemetery in the woods behind his house, most graves marked by flagstones.

A small search team crossed the broad green meadow at Elmira than headed up the wooded point looking for a century and half-old cemetery. They were searching for their ancestors' graves. Those of Andy Boone, a Civil War veteran, his wife Comfort Rollyson Boone, and Isaac "Ike" Siers.

The team soon found plain stone grave markers hidden in the oak leaves of October. The Siers' stone was marked "IS" in meticulously chiseled initials, fading over the years. The Comfort Boone stone was marked "CB". Also found hidden under her stone was a stash of acorns put there by living inhabitants of the woods.

Elmira was a little hamlet in central West Virginia, Braxton County. In Civil War days, there were only a few home sites in this headwaters area of the Left Hand of the West Fork of the Little Kanawha River, which flows down to the Ohio at Parkersburg. Isaac Siers had a cabin in the center of todays Elmira, given that name after the war. There were two other Civil War-time home sites nearby. Another one stood fairly close by, about a mile away on the woodland track to the village of Rosedale.

This old cemetery rests hidden in the hardwood behind where Isaac Siers and his family were torched out of their cabin home in the midst of the Civil War in the breakaway state of West Virginia.

The interior part of this state-to-be was the focus of early Confederate efforts to seize vital railroads and oil supplies. Failing that, it then became a hunting ground for guerrilla warfare.

Elmira and the surrounding valleys have been a pleasant peaceful place to live for over a century, but during the Civil War, these central county hills witnessed terrible rampages by outlaw bands, raids and kidnappings by enemy marauders, looting, burning and murder.

Atrocities were perpetrated by both sides. Many are the tales of betrayal of father against son, brother by brother, but none more dramatic than that of Isaac Siers by his sibling (Actually a half brother) William "Billy" Siers

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate gunners fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Five days later, Southern troops attempted to take the arsenal in Harpers Ferry. That town was also a key target because of the junction of two strategic railroads, Baltimore & Ohio and Winchester & Potomac. B&O tracks run across northern West Virginia from, as the name designates, Ohio, to Baltimore and Washington, the number one Confederate target. No railroad in those days could be more important.

The western mountain counties of Virginia had very little in common with the distant populous and powerful counties across the Appalachians. The mountaineers were apposed to secession from the Union. In fact, the western counties voted to secede from Virginia, in essence declaring their independence from the mother state. They didn't become the 35th state of the Union until June 20, 1863. At that time, there were about 3,600 slaveholders out of a population of 377,000. There were about five slaves per household. In Braxton County, there were 26 slaves owners.

On June 13, 1861, the first land battle of the Civil War was fought at Grafton, (West Virginia), a key midpoint station on the railroad. A month later major battles were fought near the railroad, resulting in Union supremacy in northwest Virginia for the remainder of the war. Control of these railroads choked supplies to the South. After a couple of initial defeats, Northern armies in the areas closer to Braxton County were able to gain control from the Confederates.

In August 1861, General Robert E. Lee led a 15,000 man army into West Virginia about three days ride from Elmira. In this, his first Confederate assignment, he repeatedly chose not to attack outnumbered Federals, and thereby missed a golden opportunity to recapture north western Virginia for the Confederacy. For these failures, he was demoted to the Richmond bureaucracy for awhile. A consolation, however, was his acquisition, while in West Virginia, of a splendid gray steed, "Traveler," who served Lee well throughout the war.

In 1862, the war in West Virginia whipsawed back and forth between Union and Confederacy. Stonewall Jackson led brilliant campaigns in and alongside what later were West Virginia counties. Two future presidents fought for the Union in West Virginia, Col. Rutherford B. Hayes and Lt. William McKinley.

Even though the Confederates could not capture and hold important territory, they led a number of successful raids across the state. In august 1862, Albert Gallatin Jenkins led over 500 men in raids that captured numerous important towns only a one day horseback ride from Elmira, including nearby Glenville and Spencer. Jenkins led his troops into Ohio, proving the tenuous hold that the Union had in this area. Confederates destroyed the salt manufacturing plants in Charleston. Toward the end of 1862, major battles took place in the eastern panhandle counties but the Union prevailed.

The year 1863 was called the year of the raids in West Virginia. Union troops controlled the state, but were unable to prevent major forays by Confederate forces. Confederate General John O. Imboden led a regiment from Staunton, Va. across eight interior West Virginia counties, in the spring. General William E. Jones led a battalion of troops to join him. They destroyed oil supplies at Burning Springs in nearby Wirt County and livestock and property throughout the central and northwest counties. They failed at their main objectives, to destroy the B&O and capture the Union loyal Virginia government set up in "exile" in Wheeling.

Confederate General John Morgan led his regiment into West Virginia in July. He was defeated by Union troops but his men retreated to the south, rampaging through Braxton and the central counties. On Oct. 13, a Southern strike force attempted but failed to take a Union fort at Bulltown in Braxton County. Finally in November, the North won a major victory at Droop Mountain in Pocahontas County.

Most of the action in 1864 in West Virginia took place in the eastern panhandle area. The biggest threat to the rest of the state was from irregulars, Southern supporters who were never mustered into Confederate service. Depending on the man, there was a variety of reasons for joining a guerrilla band. Some men joined out of high principle. Honorable men can disagree about political issues and ultimately take up arms. The issue of local and states rights versus Federal rights stirred strong emotions in these parts where men were strongly independent and hated outside control. This started as a war of ideas. Here was an opportunity to poke a finger in the eye of Northern busybodies who wanted to tell other people how to live.

Other local men joined highway robber gangs to take advantage of the situation to grab some loot. Others joined because of the perverse raging joy in hurting your betters and breaking their things. The law abiding folk had a disparaging name for those loners who pretended to be peaceful citizens but who secretly hid out and harassed enemy neighbors and their protecting armies on the other side. They called them bushwhackers.

Exact numbers of West Virginia Civil War soldiers are unknown. Union headcounts have been estimated at from 20,000 to 36,000, about 300 from Braxton County. Confederate army state counts are estimated at 7,000 to 10,000, including another 300 from Braxton County. It is estimated that over 20,000 would be counted statewide, if militias and irregulars were included. True to form, West Virginia supplied soldiers in higher percentage than other Union states.

In the next to last winter of the war Lt. Col. William C. Starr of the Union Ninth West Virginia Infantry ordered his squad of troops to mount up and head out at nine o'clock on a crisp winter night from their camp on the Gauley River in Nicholas County. They rode the long rutty wagon road downriver to the mouth of Duck Creek. Then headed up the valley toward the watershed ridge at the head of the long hollow. Two days earlier an informer had ridden in from the West Fork valley of the Little Kanawha. Troop commanders didn't consider this fellow entirely trustworthy. In fact, a couple of years earlier a team of scouts had tracked him down and ended his bushwhacking days by breaking both of his knees with their gun butts. Their duty now was to quash all sabotage and guerrilla warfare that infested this part of West Virginia and threatened the railroads vital to getting supplies to Union troops south of the Mason Dixon line.

The Federals were very frustrated by years of rampant guerrilla activity in the area. On the other side, Confederates and their rebel allies grew more and more desperate. Feelings were running very high. Any credible informant is worth listening to. This man had provided valuable information before. His name was William "Billy" Siers.

In the course of their gentle climb up from the Elk, Starrs squad forded their horses across icy meandering Duck Creek numerous times. They passed half dozen cabins that settlers had built where little streams emptied out of the side hollows. These people, or their fathers, came here from the East and began clearing the forest over the past couple of generations. The soldiers rode silently in the snow and avoided going close to cabins where families were sleeping. Thin lines of smoke wafted from banked fires underneath the chimneys. Starr guessed that it was about three in the morning when a hound dog barked from outside a cabin across a big cleared meadow close to the forks of the valley. They rode quietly on, every eye on the cabin.

At the little village of Servia, they silently headed up the left fork of the valley. A short while later they slipped past the farthest cabin in the valley and started the steep climb up toward the low gap on the ridge between the hills. Two days before, Lt. Col. Starr and officers of the Ninth Infantry detachment garrisoned at Summersville listened as Billy Siers told them about a relative or his, Isaac Siers, Ike.

Billy said that Ike had been a friend of the late Perry Conley, a Confederate guerrilla fighter who used to live at the mouth of the West Fork before he lit out to hide in the woods. Ike, according to Billy Siers was a ready supplier of hoofed wild game, dressed, quartered and salted, wool blankets and butter to Conley's still very active Moccasin Rangers band. When asked what his relationship to Isaac Siers was, Billy replied that Ike was his younger brother. When asked why he would turn against his family, Billy said that he now was fighting for the Union and with things as hot as they were, he would be killed if the Confederate partisans caught him. He was afraid that Ike would turn him in because of their strong disagreements. Not a few of the bushwhackers, like Billy, played both sides. Some on the losing side, as long as they could get away with it, would switch allegiances, keep their rifles, let bygones be bygones until it was expedient to switch again. Men like these in tribal societies hold to a standard of bravery rather than adhering to political consistency. What counts to them is how courageous you are in your own eyes. In that time, West Virginia was nothing if not tribal.

Ike's family at home included three boys and five girls. One of the boys was almost old enough to go into the military, Billy insinuated. Two older sons had already left home to join Copperhead Marauders, he asserted. The Moccasin Rangers were dangerous opponent of the Union army sent to guard the Baltimore and Ohio railroad lines running across West Virginia. They led repeated attacks on Union camps and had an extensive network of spies, suppliers, informants, and snipers.

Starr and his commanders were fed up with the partisans and their allies. They were worse than a den of rattlesnakes. You would go in and kill one or two, the rest would slither away. Then they would come back relentlessly to strike at you heel. Starr was under orders to do whatever it takes to clean them out. He concluded the session with Billy with a decision that he himself would form up a fire team and take care of this task. He wouldn't ask anyone to take on this awful duty until he had done it himself to show the way. He resolved to go across the mountains to the headwaters of the Left Hand Fork of the West Fork and eliminate Isaac Siers and his family, along with their property and all of their belongings.

With the Siers site now just barely in view, the military squad sat mounted on the little hillside point on the wagon roadway that led to the clearing at the flat bottom forks of the valley at Elmira. The Milky Way glowed muted gold in sinuous loops across the moonless winter sky. Dimpled stars seemed to push out through the blue black curtain that hung silently across the universe. Near the cabin, a small creek joins Left Hand Creek from a long hollow facing Siers bottom. A spring fed run in the hollow behind the cabin defines the circular perimeter of the clearing. Starr and his men absorbed the pleasant smell of the thin shaft of wood smoke that arose from the chimney of the oblong log cabin with its single roof.

It was a fairly large, story and a half building made of thick notched poplar logs, chinked with four inch thick sandy clay plaster. At the near end was a six foot wide fire place and kitchen, with two bedrooms on the opposite end and two upstairs. There was a doorway in the middle front, with windows on either side of it. It was a pretty place in its setting.

Scanning the snow blanketed meadow and primitive surrounding roads for a few minutes Starr then gave the command. The Union squad spurred their mounts and scrambled down off the hill. They separated at the creek. One contingent dashed across the streambed and circled around toward the back, between the rear of the cabin and the point of the hill. The other mounted soldiers swung down the wagon road, jumped the icy creek and galloped straight toward the front of the darkened house.

Someone leaped from the little second story window on the north end of the house opposite the assault. He carried a gun and ran headlong up the steep bank of the point into the woods. Two troopers cut away from the flank and stormed off after him, spurring their horses onward. This was Isaac's 16 year old son James (Jim). Ike told him to never let himself be taken by marauders. The Confederates and their so called "Copperhead" sympathizers would often shanghai young men to serve in their ranks. At the first whisper of a raid, such men would grab a comforter and head for the hills to wait until the enemy was gone. It was said that it was safer to be in one or the other army than to be a home. So the men often chose to run and hide.

The women were left alone like this to fend for themselves. The clever ones would outwit their interrogators, but they frequently had their homes plundered and their livestock driven off. After a battle, they tended to the wounded or were left by themselves to bury the dead.

The boy, Jim Siers, instantly woke when he heard threatening hoof beats, grabbed his overalls, his gun, hat and wool jacket. Before he dropped down from the window, he hissed in a soft voice, "I'm leaving Daddy, someones coming this way."

He scrambled across the barnyard, chased from a short distance by the two9 galloping horsemen, their heavy overcoats flying. The boy had a body like steel, made very strong from spring plowing, summer scything and fall threshing.

As the main body of troops reached the cabin, Jim ran up the point to the ridge, firing a shot at his pursuers. Returning pistol fire whistled over his head. Young Jim ran out the ridge, just below the skyline, shooting at the troopers who rode along the side of the hill well below him. At the next hollow Jim ran down and crossed the creek, then ran headlong up and out the Cowskin Creek Ridge. The soldiers rushed up the ridge behind him firing off a rifle shot here and there when they thought they saw a flash of movement between the trees. The boy decided to go no further in a northerly direction. There was a team of soldiers at a lookout point on Rattlesnake Knob, the highest mountain in this area.

Depending on guerrilla activity the Union Army posted from two to half dozen men up there to watch the roads to Rosedale, Nicut, and Servia. They patrolled this area and made reports on any horseman or campfires they spied out. Jim Siers couldn't risk rousing the two men sleeping in tents there now, provoking them to join in the chase. The boy cut down through a narrow hollow under the ridge and quickly hid in some jagged rocks. From this ambush point he fired on the horsemen when they appeared, as they forced their mounts down the steep embankment. Then Jim turned and ran over and up the opposite ridge while he saw from the corner of his eye that one of his rifle slugs had hit one of the men. Jim Siers escaped after a chase down the other side of the mountain, when the soldier swung off pursuit to go back and look after his comrade.

Early on when war clouds began to hover over the mountains, it was not unusual for the Siers family to see on the road above their cabin, companies of soldiers marching up the creek on their way over to the Elk River and the war theaters over there. At the end of 1861, war struck nearby at Sutton, the county seat of Braxton County. The town was burned to the ground, despite pleadings by its citizens. The invaders consisted of a detachment of Gen. John Floyds Southern Army, under the command of Capt. A.J. Tuning. The little town of Sutton, less than 30 miles from Elmira, was a stagecoach stop on an important link in the turnpikes that crisscrossed the state. Federals from Clarksburg scoured the countryside, ran down and wiped out the looters and arsonists.

The opposing groups roamed all over the central counties through fall of the following year. More Federal troops poured into the area. None the less Arnoldsburg was hit again in May 1963. In September 1863 there was another skirmish between relentless copperheads and detachment of 11th Regiment at Beech Fork, only a short ride cross country west of Elmira. During 1863 major raiding parties crisscrossed Braxton County. Confederate Gen. John D. Imboden led over 3,000 men into the county. A detachment of raiders went through only 8 short miles from Elmira, confiscating livestock and destroying anything of value to the North. They marched on to an oil refinery at Burning Springs, nearly 50 miles northwest of Elmira.

Later in the summer Confederate Gen. John Morgans men retreated south from the Ohio River at Ravenswood, eventually through Braxton County up Steer Creek a couple of ridges from Elmira. They looted and appropriated livestock as they bruited their way through the country. Col. "Mudwall" Jackson, a cousin of Stonewall Jackson, struck at Bulltown, only 35 miles from Elmira, on Oct. 13. The Union Commander refused to surrender, even though he was outnumbered almost two to one. The confederates abandoned their assault and their single four pound cannon and retreated.

A year later in September, Virginia Cavalry captured Bulltown and proceeded to destroy weapons and supplies and to confiscate horses in a continuous raiding foray on their way back to Virginia. Confederate troops remained active in Braxton County area through the close of 1864 near the end of the war. Fort Moore in neighboring Gilmer County, was burned down by them in December of 1864.

At the Siers cabin, the soldiers surrounded the house. Ike Siers yelled for his family to get down on the floor, fearing that whoever it was would start shooting. The soldiers commenced knocking out windows with their rifle butts. They broke away frames, ripped down the flax curtains and climbed into every window. Other men stayed watch to make sure no one else escaped the house. One of them shot Ike's old hound dog in its kennel. Two men knocked down the front door and a third burst in amidst the now hysterical family.

"What the hell are you men doing here?" Yelled Ike Siers: as he leapt up from the rag rug on the floor. He glanced at his gun hung on pegs over the fireplace, but thought better of it. His wife Isabel jumped up and lit a kindling taper then a tallow candle on top of the dry cupboard. Their house full of children were forced down from the loft or roused from under their rope cord beds along the cabin walls. The baby, Paulina Isabel "Piney", standing in her flannel nightdress with her feet planted apart holding her cornhusk stuffed rag doll, pleaded with the officer, "Please don't shoot us mister, please don't shoot us!" She ran behind her mother and hung to the folds of her night skirts, peeking around at the blue uniformed officer.

Lt. Col. Starr ordered the family out of the house. Meanwhile the soldiers remaining inside proceeded methodically to smash furniture, beds, baskets, crockery and utensils. They grabbed smoked meat, corn meal, flour, salt, and foodstuffs and jammed them into gunnysacks; then in a few moments took them outside to sling over their horses flanks. The family was roughly pushed through the broken doorframe and made to stand against the front cabin wall facing six soldiers and the commander.

Finishing their destruction inside, four more soldiers came out the door and proceeded over to the barnyard. They shot the family milk cow and a hog. Chickens, geese and a few sheep were easy pistol targets. They knocked over and smashed bee gum log boxes with hibernating bees inside. Ike didn't have a horse. He had long since traded it off to keep from losing it to marauders.

Two teenage Siers daughters, Susie and Sarah, sobbed quietly clinging to their parents. Martin, a young boy and the other youngsters wailed plaintively, and four year old Paulina whimpered through her tears, her forehead wrinkling up with her plea, "Are they going to kill us all Mommy?" Despite early morning cold, fear driven perspiration plastered the little girl's curly black locks to her china doll forehead. Her bright red lips and strong blue eyes were brilliantly highlighted by the dawning pink sky.

William Starr and his men surrounded the family, who stood with their backs to the big square logs of the cabin. The Union Soldiers, weapons at the ready, stood in the chip yard in front of the house, now made muddy in the snow by the trampling of many boots and hooves. A couple of the men held pine knot torches that they had grabbed from beside the fireplace and lit in its coals. Starr brushed crusty snow off a thick log chopping block. He sat down on it as the brightening dawn sun was slowly painting its way down the hills and across the valley as it arose on the eastern side of the mountain behind the Siers cabin.

Starr never questioned his duty. He always executed general orders as expected. He was deliberately chosen for this task of rooting out partisans because it was a very hard thing to do. He had children of his own, not many days' ride away up near the B&O where the war first started in West Virginia. Regrettably, these were people of his own kind, not the usual scalawags he dealt with and was expecting. Now, little Piney's pathetic fear was beginning to trouble his heart. He struggled to focus on his assignment.

The populace of Braxton County and this area of western Virginia were split between passion for the South and those for the North. About 300 Braxton County men were recruited into Southern Armies. Many more left the county to join rebel companies in other counties. Many men also stayed at home to protect their families and goods. Perry Conley, a young notorious bushwhacker, or Robin Hood, depending on your point of view, took command of neighboring Calhoun's so called, County Home Guards. Conley, by some accounts lived for a time at Minnora, a short ride from Elmira. He struck fear in the hearts of men even before he became a marauder. A natural leader, he was six feet three, very strong and relentless. He never gave up. He wanted to call his band guerrillas, but they preferred to be called the more common "Moccasin Rangers." That name caught on and that's how they were generally known.

These men, and other Southern sympathizers, seized the military initiative soon after the start of the War in 1861. Women weren’t excluded from the Rangers. Conley had a cunning female, Nancy Hart, riding with his gang. She helped plan raids, spied the opposition, was an expert shot and fine companion for Conley, while his wife and children languished at home. A number of guerrilla bands operating under local strongman captains were organized and soon spread terror among citizens loyal to the Union. The fact is that such outlaw gangs existed well before the war. For example, the so called "Hellfired Band" of neighboring Calhoun County in about 1842 murdered Jonathan Nicholas, a county official in charge of road building. It is equally alleged that remnants of the Rangers continued their criminal ways after the war, notably the Boogerhole gang across the ridges in neighboring Clay County.

Sizable Federal force was required over the course of the war to keep the bands of deserters and irregulars in check and to guard loyal families and their property. They considered the irregulars as outlaws, rather than soldiers. The irregulars, however, did subject themselves to Confederate command when the army was in the area.

Meanwhile, their fundamental military objective was to operate in small detachments behind Federal lines to thwart Federal scouting parties and foragers, but they also rode roughshod over the families loyal to the Union.

At Arnoldsburg in Calhoun County, a little over 20 miles north of Elmira, on Nov. 28, 1861, Captain Perry Conley's band of Southern partisan rangers attacked a detachment of Captain James L. Simpson's volunteer Company C. Eleventh (West) Virginia Infantry that soon after were mustered into Union service. A lot of ammunition was expended but to little effect. Losses were light on both sides. After a short skirmish, the partisans faded back into the hills, the soldiers returned to their base near the town of Elizabeth, but not until they dispatched one of Conley's wounded Rangers. Several of the soldiers fired on the immobile man at point blank range. This incident played no small part in the result that this area stayed largely under control of the partisans. Local government was non existent. Anarchy reigned. Stores were ram sacked, post offices were closed.

Conley's partisan band robbed and murdered. It was every man for himself. Terror reigned rampant for the first couple years of the war. Soldiers returning home in the winter to visit their families risked being quietly whacked from the bush by their neighbors, if their home country was in opposition's hands. Conley, whose name alone brought terror throughout the central counties, was soon killed in battle with Federals in nearby Webster County in the summer of 1862. In fact his brother James Conley, a union soldier, shot him to death.

Calamity sealed by tragedy, Guerrilla activity continued onward until the end of the war, unremittingly combated by patrols of the West Virginia 10th Regiment Infantry. A dramatic guerrilla shootout took place at one of Ike Siers' neighbors home, a few hours walk east. Milton and Amanda Rose Frame's Tate Creek homestead was assaulted in 1861 by seven marauding rebels, who came to their farm intending to capture Mr. Frame and to confiscate their fine horses. The Frame family took up battle stations in their little cabin. Angry shots were exchanged. Suddenly a Rebel bullet wounded her fighting son, a youngster who had removed a shingle from the attic roof to fire down on the bushwhackers. He got his curly locks parted by a Rebel bullet. This infuriated Amanda Rose Frame. She fearlessly charged out among the Rebels, blasting away with her deadly revolver. Firing back, they wounded her in the hand. Those that she hit had to be carried away.

In the cold February dawn, Isaac Siers stood with his terrified family in the snow in front of his cabin. They were in their nightclothes and without shoes. Officer Starr sat a dozen feet away on a piece of log used as a chopping block. He toyed with his pistol in its holster. The Siers family was shivering from fear and from cold. The children wailed and sobbed.

Finally Siers said, "If you’re going to shoot me, go ahead and do it, but spare my family." Shuddering out a quiet little sob, baby Paulina had by now calmed down a bit. It was as if she saw a gentility in William C. Starr that no one else could see. When she heard her father speak, she slowly walked over from the house to the Colonel. Her mother made an attempt to stop her by the shoulder, but the pretty little girl would not be deterred. All eyes were on her. She went up to Starr and put both little hands on his knees and looked up at him. He reached down and lifted her up.

"You're not going to shoot my daddy, are you?" She said as she tilted her tear streaked face to one side, looking at him with her big piercing eyes. It was all he could do to strain his voice to speak what he next said. "I have orders to shoot you all, little girl." Siers roared again, "Shoot and be damned, I'm tired of setting here. If you're going to do it, get it over with. Shoot me now, but let my wife and children go." When pressed to the wall, Ike was as tough as an old pair of boots. All eyes were now on Starr. He sat for a long while, looking at nothing, doing nothing, as if in another place, another time. With the girl in his lap, his hand on her warm back, he uttered slowly, looking at Siers, "I'll give you ten minutes to get out anything that you can carry, then you all get away from here.

Paulina jumped down and ran to here mother. Starr pulled out his watch. The family scrambled back into the wrecked house and rushed to put on warm clothes and shoes. Quickly, they grabbed as many quilts and covers as they could carry.

Rushing about, they took the iron fireplace cooking pot, big Skillet, a Dutch oven, and anything else not broken, the bible and as much more as they could carry. Siers grabbed his hunting rifle, a saddle, and his whiskey jug, they all jumped out the door.

"I'm going to spare you on account of your children," said T. Col. Starr slowly. "Now get out of here and consider yourself lucky, you goddamn Copperheads," he snapped. Isaac Siers looked quizzically at Starr. He'd been called many things in his day, but he'd never outright been called a Southern sympathizer before. Many border-state men were split between their allegiances. The natural rebelliousness of mountain men made them sympathetic to Southern audacity.

West Virginia men distained the smug gentry of the east, who controlled too many aspects of their lives from too far away. Despite being tugged to and fro, Isaac Siers finally came down for the Union. Now his evicted family rushed off quickly for shelter up the hollow across the meadow to the nearest neighbor's cabin. As they left, Starr gave orders and his men spread coal oil and kitchen grease across the puncheon floor. They lit the fires with hot ashes scattered from the fireplace. They stacked and lit wood slats and shingles at the corners of the house and in the window holes. They busted down Siers' rail fences and banked them up against the corners of the stone chimney and the edges of the cabin.

Isaac Siers and his family watched roaring flames consume their once peaceful home as they headed up the hollow toward Walker Creed ridge in the now brightly fierce, fully risen sun. Their neighbors ran out to meet them. They all watched a plume of smoke rise from the house like an angry black fist. As the flames died down, Jim Siers' pursuers, one bandaged, rejoined Starr and the others. They dressed out and roasted Siers' hog on the hot coal pile, the remains of their cabin. All that remained for a hundred years at this site was Ida Isabel Siers' flowers rising anew every spring in her yard.

Early on in the war, Billy Siers had a hideout up the hollow from Elmira. Billy found a natural kind of cave in the rocks at the head of the hollow on the Walker Creek side. He piled up an ordinary looking cover of brush and leaf over it and used it to hide his horse away from raiders. Billy had a family and a son also named Billy. Some people came to call Old Billy "Coppernose" and his son "Young Billy." Young Billy joined the 14th Virginia Cavalry in 1862. He was assigned to spy duty in Braxton County. Father and son then both used the cave as a hideout.

After Old Billy Coppernose was kneecapped, Young Billy was on his own. Ike Siers and his family knew, when they were burned out, that Young Billy was up in the "Billy" rocks, but no one said a word to the soldiers.

After the war, Old Billy Coppernose Siers was living on Walker Creek with a different family. Late in life, it was made an honorable union. Young Billy went on the serve in Eastern Virginia. After the conflict was over, he came back and also lived out his life on Walker.

Their unforgettable names and exploits were so associated with the little valley leading up to the rocks that is was popularly memorialized as Bill Fork. Most mountain men and women surreptitiously admire a rebel.

Why would Old Billy Siers strive to bring about the death of his brother, or more specifically his half brother? Why would he devise to have his sister in law Ida Isabel, his nephews and nieces killed? Billy was the first born in his family but he was not conceived in that family. Perhaps he was not the child of both his parents James and Francena "Franky" Roach Siers. Did this happenstance impact his character? His half brother Isaac possessed a very desirable piece of property at the crossroads of the upper Left Hand Valley, later Elmira. Was it inherited? Any man of that time, or later time for that matter would naturally desire that beautiful piece of bottomland.

Isaac was primarily a hunter. He didn't care much to work the land. Like Cain and Abel, and even Esau and Jacob, was there in Ike and Billy the inborn conflict of the farmer for the hunter? Like Ishmael and Isaac, was there the resentment born of the favor given to the younger child? Was the root cause envy? Anger? Resentment?

Brother against brother is a metaphor for many of mankind's wars. This was certainly true of the American Civil War. In the Border States and in West Virginia, it truly was in many families, brother against brother. The war split families, broke friendships. It left hatred that lasted for more that a generation. It dominated political passions.

Republicans were synonymous with the North, Democrats with the South. Later generations assumed the poisonous anger for the sake of peace. During the war years, idle talk was dangerous. After the war, it was best to forget. Over the years, the survivors talked less and less about it to the extent that much of the detailed knowledge of the war in this area was lost to memory.

In this case, of this much we can be sure. Billy Siers almost succeeded in the destruction of his brother Isaac and his family on that dark winter night at Elmira, when the place was burned down to the ground.

From The Adventures of Young Billy Siers, A Sentry for the Confederate Army:

During the Civil War, the armies took most of the horses, so Old Billy Siers hid his horse, named Old Puss, up in the rocks where there was a natural shelter and where no one would see it. His son, called Young Billy Siers, had gone away to the war and joined the Confederate Cavalry, but, since he was little and quick, they made him a spy, called a sentry in those days, and sent him on back home to spy on the Yankees who was coming through these parts. Young Billy camped up in the rocks, since called Billy Rocks, and hid with Old Puss where he'd be safe from the Yankees catching him. The Yankees almost caught him. They caught his father and knocked his kneecaps down for keeping spies for the South. That's so he couldn't get around. They also took his brother Isaac up the holler to shoot him, and Isaacs children, Martin and Phiney, followed crying. Shoot and be damned, I'm tires of setting here, Isaac shouted after waiting for the Yankees to make up their minds. They finally let him go because of his kids, but no one told on Billy, and he remained safe up at the rocks with Old Puss.

Later, he left out of there. He went to Charleston and then on to the Dismal Swamps to fight there. He and the men he was with hadn't had anything to eat for seven days. Young Billy overheard the other men and then his own bunch, say they were going to get the smallest man, which was him. He hid that night and escaped from being eaten. They survived on gourds for I don't know how many days. Billy survived and returned back to Walker, until his death. He had three children, Morgan, Becky Ann and James.