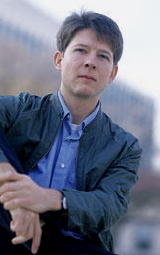

CALHOUN NATIVE JED PURDY'S HOMESTEADING DAYS - University Professor And Author Has Made His Mark

Calhoun native Jedediah Purdy wrote an essay for the former West Virginia Scholars program at Woodlands Institute, which he attended in 1991 while being home-schooled in Calhoun County, which is re-published here.

Calhoun native Jedediah Purdy wrote an essay for the former West Virginia Scholars program at Woodlands Institute, which he attended in 1991 while being home-schooled in Calhoun County, which is re-published here.Purdy was born in 1974 at Chloe, and is now a professor at Columbia, formerly professor of law at Duke University and the author of several widely-discussed books including "For Common Things: Irony, Trust, and Commitment in America Today" (1999) and "Being America: Liberty, Commerce and Violence in an American World" (2003).

Purdyâs new book, "This Land Is Our Land: The Struggle for a New Commonwealth," is shorter, more pointed. Itâs about how to live together once weâve accepted that there is nothing more “natural” than living in society with other human beings, in a world in which politics and ecology have come to be one and the same.

He is also the author of "The Meaning of Property: Freedom, Community and the Legal Imagination" (2010) and "A Tolerable Anarchy: Rebels, Reactionaries, and the Making of American Freedom" (2009).

Purdy teaches constitutional, environmental, and property law and writes in all of these areas. He also teaches legal theory and writes on issues at the intersection of law and social and political thought.

He is the author of numerous books, including a trilogy on American political identity, which concluded with A Tolerable Anarchy (2009), all from Knopf. The Meaning of Property appeared in 2010 from Yale University Press.

He has published many essays in publications including The Atlantic Monthly, The New York Times Op Ed Page and Book Review, Die Zeit, and Democracy Journal, and his legal scholarship has appeared in the Yale Law Journal, University of Chicago Law Review, Duke Law Journal, Cornell Law Review, and Harvard Environmental Law Review, among others.

Purdy graduated from Harvard College, summa cum laude, with an A.B. in Social Studies, and received his J.D. from Yale Law School.

He clerked for Judge Pierre N. Leval of the Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New York City and has been a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School, an ethics fellow at Harvard University, and a visiting professor at Yale Law School, Harvard Law School, Virginia Law School, and the Georgetown University Law Center.

He is the son of Wally and Deirdre Purdy of Chloe.

Deirdre Purdy is a former member of the Calhoun Board of Education, leading a controversial battle against the consolidation of small community schools. Jedediah was caught up in the affray in articles published at the time in the Calhoun Chronicle, with accusations of witchcraft.

Purdy remains grateful for his Calhoun roots.

"Homesteader"

Jedediah Purdy

Chloe, WV 1991

Ah, the icons of an American upbringing! Television, video games, soda pop and ice cream, waiting for Dad after work, dressing for church on Sunday, the first day of kindergarten ... well, how about the secure brightness of electric lights, memorizing the family telephone number, learning how to flush the toilet?

Forget it.

Try public radio on an old transistor; the warm, dim glow of gas lamps; and nighttime trips to the outhouse. Try playing naked in the creek, reading by an old gas heater, and putting up loose hay by hand. These things were my youth, and I loved them all.

Mom and Dad moved from Pennsylvania to an abandoned farmhouse in West Virginia in 1974, following a dream of sufficiency and independence.

They spent the summer rebuilding floors and walls, planting a garden, and learning the techniques of scything and horse farming from an elderly neighbor. I was born that winter, in a blinding snowstorm on the night of a full moon, into a world beyond the pale of most Americans.

We had no electricity or telephone, and I didn't miss either in the least. Gas lamps were comforting, after all, and I had no reason to call anyone.

If power was truly necessary, usually for carpentry of some kind, I heard the roar of our huge military surplus generator, a dark and mysterious beast that lived in a shed of its own and was usually covered by an ancient tarp.

Its sound often reverberated behind the NPR adaptations of such stories as The Hobbit and, star wars that I listened to nightly.

The outhouse, too, was nothing unusual. We had a nice two-seater, one on a sort of chair, the other simply a hole in the floor, while many of my friends could claim only one.

It was among my favorite places, and I sometimes spent hours sitting on the elevated seat, reading and enjoying the warmth of sun through the window.

The influence of the lower hole, called the "squat hole" because it necessitated such a position, caused me to wobble precariously on my feet upon toilet seats for several years before I became comfortable with sitting down.

My parents were at something of an advantage in their homesteading efforts, both because Dad had genuine farming experience, having grown up on a dairy farm, and due to the back-to-the-the-land community that existed in our neighborhood.

Some of my earliest memories are of tagging along as thirty or so long-haired adults joined in communal work crews, clearing brush on hillside farms or harvesting loose hay with rakes and pitchforks.

There was usually a potluck meal afterward, and I retain images of vegetarian quiches and jars of cream left in deep pools in the stream to cool in preparation for rhubarb pie.

The sense of community that pervaded those early years extended beyond shared work to a deep sense of hospitality.

It was not uncommon for a friend or neighbor to drop by, often unannounced and on foot, and stay for a night or two. One night, a lone New Zealander appeared at our door in search of a different family and ended up joining us for a week, working on the house with Dad in an informal exchange for bed and board.

As the years wore on, the effort and responsibility of shared work began to wear thin, and the community grew apart a bit.

We continued to farm, however, milking and butchering cows, and haying and plowing with our Percheron work horses.

I often accompanied Dad through the fields to feed the horses or milk our old Jersey, or went into the garden with Mom to weed or harvest tomatoes.

The great majority of our food was home-grown, and among my fondest sensual memories is of Mom's fresh-baked whole wheat bread, still warm from the oven, smeared with homemade butter and strawberry preserves.

At the time, I had no idea that there was anything unusual in my upbringing.

That my playmates had such names as Mountainstar and Love Child was to be taken for granted, as was the fact that almost all of my clothes had been handed down by older cousins.

We would have been considered poor, I suppose, but that meant little to me then. My friends, after all, shared my lifestyle, as I imagined most of America did.

I watched television only a few times a year, at my grandparents' home or in the living room of a neighbor who exchanged viewing privileges for fresh milkweed stalks from Hannah and me.

Soda was so rare that once, when I saw a man who resembled Dad from the back reaching into the soft drink cooler of a local general store, I rushed up to him, babbling, "Oh boy! How many are you buying? One for each of us?" before realizing my mistake.

Although I didn't realize it then, the attitudes and values with which I was being instilled were very different from those usually endorsed by the culture at large.

When I asked Mom about the brightly colored drinks I saw flowing in a small restaurant, she replied that they were poison.

I accepted her answer, but wondered for years why anyone would choose to have poison on public display in an eatery.

In another incident, when I was perhaps five, an aunt asked me whether I liked hot dogs. I replied gravely that, "They're good, but they're not very good for you." That view of junk food, although somewhat tempered, remains a basic part of my existence.

More significantly, my concept of work has been molded into a rather atypical one. For the first ten years of my life, my parents were employed outside of our home only sporadically, Dad as a Welfare Department caseworker in Spencer when I was two or so; Mom as a Charleston secretary five years later.

During these times I missed them deeply and felt robbed by their absence. As far as I could tell, they performed no useful purpose when they were taken from me.

When they were at home, however, I could see Mom typing away at the abstracts she wrote for various government agencies or hug Dad as he came in from the garage or fields, covered with hay and sweat, I felt a deep connection to their work.

I saw the results of what they did on our farm, and the pride they took in their work, and those things made it valuable to me. To this day, I view employment with suspicion, usually as little more than a necessary evil, while work at home for oneself holds a place of deep respect and nobility in my mind.

It is not a philosophy of irresponsible indolence that my early years led me to form, but rather a strong belief in independence and self-reliance and a desire to taste the fruits of my own labors. Such was the creed of the homestead movement, and it has left a strong mark upon me. - 1991

Time Bomb: 238 years after its first birthday, America is in deep denial By Jedediah Purdy

I Understand Nothing By Jedediah Purdy

CALHOUN'S JED PURDY: "Jaded Nation In Noisy Denial"