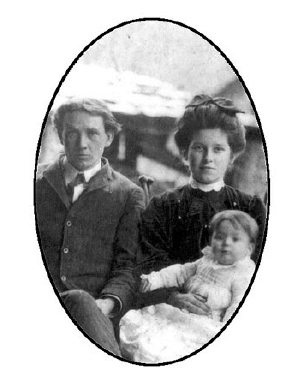

Frank and Emma Burns Weaver and Baby

(Photo courtesy of Gladys Weaver Stump)

By Bob Weaver

Abandonment by a parent is perhaps one of the most traumatic events experienced by children, although in the 21st Century divorce is common place, with half of all mothers and fathers single-parenting.

It was a pain that never left my dad, Gifford Weaver (1913-2000), nor his sister Gladys Weaver Stump (1903-1999).

During their adult life, the recollection of their mother's sudden departure would bring a painful quiver to their voice and tears to their eyes.

"I came with my dad, then in his late 80s, to the remote, narrow Wildcat Hollow, resting between the left fork of Sycamore and Sassafras Ridge. On that day we walked near the empty space he was born, telling about his mother permanently walking away from him in 1913, a small baby at the time, never to return. Sitting on a rock, he wept openly of that pain." - Bob Weaver

Despite long lives as hard-working, loving family people, imbued with Christian teachings, they reached some level of forgiveness for their mother, who walked away from their home and left them while children.

But that hurt remained until the day they died.

Gifford was a babe in arms in 1913 when his mother packed her bags and left their humble dwelling on a cold winter day, a small house in Wildcat Hollow in a thick and remote woods between Sassafras Ridge and Sycamore.

Their father Franklin Delbert Weaver (1881-1933) was teaching at a one-room school where he boarded, when his wife Emma left with her boyfriend to live in Akron, Ohio.

They had married in 1903, ten years earlier.

The Weaver's were living in a tiny house on

The Weaver's were living in a tiny house on

one of the few flat places in Wildcat Hollow

Gladys, who was only 10, her sister Jean and brother Glenn, wrapped Gifford in some blankets and walked up the hollow to Sassafras Ridge, where their father's parents, Wilson and Virginia Poling Weaver lived in a large two-story farm house, seeking comfort from the painful event.

It was there the family sheltered and re-grouped, although their father fell into a deep depression, becoming a man of few words.

In their early marriage, Frank took a teaching job that no one wanted, a remote one-room school in the black Hicks community, a few miles from Grantsville. Frank and Emma boarded there for a couple years, the black community's first teacher.

The marriage was undoubtedly fraught with money problems and the strains of one-room school teaching, teaching jobs often great distances from a home place, required leaving early and getting back late, either by foot or horse, or having to board nearby.

Gladys assumed the role as my father's caretaker, and helped raise him to manhood, while Frank continued to teach and later was Superintendent of Schools in Calhoun, remarrying and rebuilding his life with Mabel Rothwell, they had five more children.

Gladys, as she aged, would speak about the cultural taint of divorce at that time, saying "I didn't know a single person that got a divorce."

She tearfully recalled her mother stationing her down the road to warn her if someone came up the hollow while one of her mother's boyfriends visited.

Glady's mother told her to loudly sing a hymn if someone came up the hollow, and she dutifully complied.

Frank Weaver died in 1933 at the age of 51 of meningitis influenza, his Pine Creek house and farm was then to be repossessed by the bank during the Great Depression.

Years later, my dad and Gladys would get in a car and make the long trip to Akron to visit with their mother, who had remarried, working on reconciliation.

She died in the late 1940s, suffering from complications related to diabetes.

Now, I know dozens of people and children, some who have never met or barely remember their absent father or mother, and when I hear their story, I reflect on the ill-fated life of my grandparents and the pain it inflicted on the children.

|