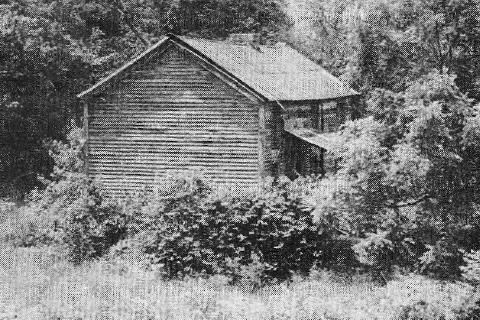

Early photos of historic Starcher-Gibson homestead with

logs covered by clapboard, if only the house could speak of

Calhoun's earliest families connected to the site, what tales

could be told about their trials, tribulations and victories

The ruins of the 1835 Starcher-Gibson house barely remain in

2011, located in a narrow hollow near the West Fork of the Little

Kanawha between the mouth of Sinking Springs and Jesse's Run

By Bob Weaver 2007

Many of Calhoun's earliest families are connected to a log cabin constructed by Adam and Phoebe Cogar Starcher at Altizer about 1835. It is the most historic dwelling whose remnants remain in the 21st Century.

Col. D. S. Deweese in his "Recollections of a Lifetime," recalls that Adam Starcher (1808-1881), "lived on and died on a very fine farm which by dint and energy of his own labors he carved out of the wilderness."

Adam Starcher was a son of Phillip Starcher, said to be the first permanent settler of the county in 1810. The Phillip Starcher homestead was along the West Fork of the Little Kanawha in the Altizer community, what was later known as the George Lynch property.

A short distance away from his father's homestead, Adam Starcher (1808-1881) built a log home (Starcher-Gibson House) about 1835, after marrying Phoebe Cogar (1814-1899), daughter of J. Peter Cogar (1753), a veteran of the American Revolution and early Calhoun settler about 1815.

Peter Cogar was at Point Pleasant when Cornstalk was killed and

was also at the siege of Yorktown. His military career ended in 1781

when the British surrendered.

He served under General George Rogers Clark in the historic conquest of the Northwest in the Illinois Expedition, the famous Lewis-Clark expedition. He likely came to Calhoun about 1815.

Peter Cogar was married to Mary "Polly" Mucklewain (McElwain), a sister of Tunis Mucklewain (1773-1851), who was also an early Calhoun comer, living along the West Fork a few miles downstream.

Adam and Phoebe Cogar Starcher had several children, including Sally, Thomas, Jacob, William, Henry, Peter Simon, John Jehu, Mary "Polly, and Elizabeth "Betty," who married Civil War soldier George Gibson and inherited the property.

Log house was fired upon during Civil War with evidence

of bullet holes, tangled remains of heavy beam logs

Starcher-Gibson cellar house still standing, with old saddle

resting on beam that could have belonged to Lt.George Gibson

George W. Gibson (1840-1923) was born in Bath County, Virginia on the Cow Pasture River. His father was David Gibson and his mother was Mary Ratcliff, daughter of a wealthy Virginia land and slave owner.

George had a brother, William, who settled near Burning Springs and five sisters, with two or three dying from tuberculosis. His sister, Jane, married James Maze and lived in Wirt County.

George Gibson enlisted for a three-year period as a private in Captain George Downs' Company of the Virginia Cavalry not long after the start of the Civil War. He was later commissioned a second lieutenant in Company A, Nineteenth Regiment, Virginia Cavalry.

During the Civil War, Gibson was at the Adam Starcher home with two of Starcher's sons. The men participated in a corn-shucking, quilting and dance, at which time George met his future wife Elizabeth, who was about 14-years-old at the time.

Yankee soldiers heard about the Rebels presence at the Starcher house and surrounded it. George jumped out a high window and ran to the hill and escaped, yelling at young Elizabeth Starcher, "I'll be back for you."

The logs of the house were filled with bullets from Yankee rifles, with the evidence remaining to present day.

Starcher's wife had several beehives and the Yanks took every bucket Phoebe Starcher had and filled them with honey, kicking over the hives and destroying the bees.

Three Yankees were killed that day on the property, according to an account by Gibson's second wife, Esther Naylor Gibson.

Starcher had about thirty head of hogs in a field where the dead soldiers lay, and Starcher made a fence around their bodies with rails and somebody rode horseback to the "Neck of the Bend" (Big Bend) to notify their families to come get their men.

The Yankee soldiers discovered a loom with a blanket Phoebe Starcher had nearly finished. "They cut the blanket up and took the pieces, also taking her quart milking cup. As they departed, one Yankee wrapped a piece of the blanket around him, departing downstream, holding the milking cup in front of him," according to Esther Naylor Gibson.

The community got word that the soldiers were disturbing people as they headed down the West Fork to the old Ball farm, about six miles north of Arnoldsburg.

Two were shot and killed at the Ball place, including the soldier with the blanket and milking cup, which was then filled with his blood.

Word was sent to Adam Starcher asking him if he wanted the blanket returned, which he declined. The Yankee soldiers were buried above the Ball barn, those graves recognized in more recent years by future landowner Quinton Morgan. None merited burial in the nearby Winner-Ball family cemetery.

The Winner-Ball Cemetery contains the graves of Tunis (1773-1851) and Katherine (1772-1849) Mucklewain (McElwain, Wayne) early Calhoun settlers.

Lt. George Gibson was captured and imprisoned for eleven months at Camp Chase, Ohio, near Columbus.

Gibson had a buddy who attempted a tunnel dug from under their bed, but word got out about their planned escape and the tunnel was discovered.

Gibson assumed responsibility for the attempted escape, asking the Yankees not to shoot his fellow soldiers, and Gibson was ordered to commence replacing the dirt in the excavated tunnel, with no food, drink, or sleep until he had the job completed. He spent three days and nights tamping the dirt back.

Gibson's father, David, was a Confederate soldier and died during the last eight days of the Civil War at Big Bend. His house at Big Bend was surrounded with Yankees and David fled to the riverbank to hide, but was quickly located.

He was shot in the foot and pleaded to the soldiers not to kill him, but to no avail. He was buried in the Big Bend area.

At the end of the war, when word of the exchange of prisoners was announced, his was the first name called out, recalled his second wife Esther.

"He was told to cook up three days rations. He put two bushels of biscuits in a meat sack and headed south, assuming he would be accompanied by somebody with a complementary food selection that would offer a variety in diet, however, not one other exchanged prisoner of his outfit was called out, so his biscuits were his steady fare." wrote Esther Naylor Gibson.

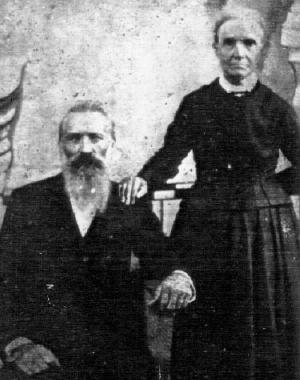

George Gibson's father, David Gibson and wife of Big Bend, who was killed running from soliders at the very end of Civil War

Starcher, after saying "I'll come back for you"

He was discharged and went to Louisiana where he secured work napping iron ore, after which he returned to Calhoun to reunite with his girlfriend Elizabeth "Betty" Starcher. He married her in 1865, she was about age 16.

The Starchers had little variety in food outside of meat and bread so George gave his fiancée $50 from his earnings, she and her brothers went by horseback to Burning Springs to get more festive food for the wedding dinner.

Gibson was employed as a government land agent, writing deeds, with he and his wife making their home with his Starcher in-laws, caring for them during their old age, after which they inherited the cabin and land.

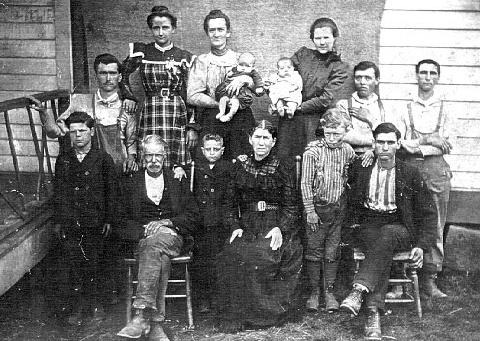

George and Elizabeth Starcher Gibson family at homestead,

First Row (L-R) Unknown, George Gibson, Unknown, Elizabeth

Starcher Gibson, Unknown, Unknown; Second Row (L to R) Pete

Starkey, Virginia Gibson, Florence Gibson, Unidentified Infant,

Unidentified Infant, Elizabeth Gibson, Wes Craddock, Amos Gibson

George Gibson and his wife Elizabeth "Betty" Starcher had 12 children, Mary B. Whyte, William F. Gibson, Adam Poe Gibson, Almira Gibson, George Gibson, Jr., Freddie Gibson, Amos Gibson, Warren Gibson; Elizabeth Starkey, Virginia Stockwell, Cisco Gibson, and Kay Gibson.

Gibson spoke at a number of political meetings, and President William Jennings Bryan sent Gibson an autographed picture of himself, and to Mrs. Gibson he sent a five-dollar gold piece. After her death in 1902, Gibson applied the gold piece on a monument for his wife.

Esther Naylor Gibson (1888-1983) early photo and photo before her

death, was George Gibson's (1840-1923) second wife, marrying him in

1903 when she was about 16-years-old, Esther's keen recollection of

her Civil War husband was dutifully recalled until her death at 96

Gibson, then 54-years-old, married Esther Naylor in 1903, a girl about 16-years-old. Gibson and his new wife then had six more children in the log house, with Gibson dying in 1923.

Esther Gibson lived to the ripe age of 96, passing in 1983, she continued to spend much of her life in the historic Starcher-Gibson homestead.

She was one of Calhoun's treasures, having delivered over 200 babies as a midwife and contributing much information to the repository of Calhoun history.

The Starcher and Gibson families repose in the Gibson

Cemetery on the hill adjacent the Starcher-Gibson homestead

The information for this article is from Esther Gibson, "Calhoun County in the Civil War," and other sources.

The book, published by the Calhoun Historical Society in 1982, was dedicated to her. "Esther's exceptional memory has allowed her almost complete recall in relating Civil War stories," the dedication said.

|