WEAVERS: AMONG FIRST SETTLERS OF KANSAS - "Good Lord, We're All Going To Die"

The Weavers left (West) Virginia in 1854, among 14 wagon loads of family and neighbors, to build a life in the newly opened Kansas territory, a journey of hardship, courage and grief

This is the story of Daniel Weaver's effort to settle in Atchison, Kansas in 1854, traveling from Barbour County, Virginia (by way of Gilmer County).

The Weavers were among the first white settlers in that territory, with Native Americans still roaming their lands, being pushed out by the westward expansion.

Daniel's brother, John Weaver and his family, settled in New Virginia, Iowa.

This account was written by young Benjamin Weaver (1835-1904), about 20, son of Daniel (1801-1856) and Mary Mitchell Weaver, whose story is one of perseverance and survival.

While this story is about the Weavers, their contemporaries were also hardworking and persevering men and woman, who we should hopefully remember, including the Polings, Hathaways, Proudfoots and Robinsons, among others, some who went west, but many settling in Calhoun and Gilmer counties with the Weavers, coming from Barbour County. - Bob Weaver

THE JOURNEY

When I, Benjamin Weaver, was a young man, about 20 years of age, my father, Daniel Weaver, was a well to do farmer in Barbour County (Virginia) in what is now known as the Talbott Community. He owned 200 acres of land.

In the fall of 1854, he sold his farm and went to Kansas, taking his family, that was still at home with him. The children who were at home were William, Eugenous, Cassandra, Almira, Adeline and Benjamin (writer).

We traveled by the way of oxcart and tent wagon. We used both the oxen and horses. We drove the cows along with us so we would have milk to drink.

We went to Gilmer County and stopped at my brother Johns, who was married and lived near Parkersburg (likely near Tanner, Gilmer Co.). We rested our animals there for a day or two, then we crossed the Ohio River and proceeded on our way. We would stop and rest for days at a time. It took several days to make the trip.

Winter overtook us in Iowa, the fall of 1854, and we were forced to spend the winter there. In the spring of 1855, we went to Kansas Territory. It was not yet a state.

We settled ten miles west of Atchison, Kansas and took our claim. Atchison was a small place at that time. A tavern owned by Mr. Allen, one grocery store and a dry goods store, a drug store and three small dwellings completed the town.

When my father settled on this claim, there had been no surveying done and we did not know where the lines would be. We were located on a little creek, which was known at that time as Camp Creek. There were four claims at that time, in this place and we had some fear that when the government surveyed the land that we would be cut off from our claims and some of our crops that we had put out. If so, our neighbors would get all our crops.

I, Ben Weaver, took a claim on what we called at that time, Mormon or Crossroads, running west from St. Joseph, Missouri. We plowed twenty-five acres on my claim and about five acres of my father's claim on Camp Creek and then built a house on father's claim. This work was done in the spring of 1855.

After we got some corn planted, I went to work for a man named Pensino, a Frenchman, who had married a Pottawatomie squaw.

One day I went to Pensino's to put up some hay, taking my brother, Eugene, with me. We heard a terrible whooping and yelling among the Indians. I thought of Wampon and Peter Parley. I had heard of their trouble with the Indians. I thought perhaps that Wampon's great grandson was in the camp and that he was going to play that I was Peter Parley.

I told Eugene to go up to a high knoll and see what was going on. He returned in a short time, saying that the Indians were fighting and killing each other. It was about two o'clock in the afternoon and we had no dinner yet. I lay my scythe down and went up on the hill to ascertain their meaning.

I had never seen an Indian before we came to Kansas. I began to think there was war in the camp, without a doubt. When I got close enough to see, I discovered they were all drunk. Not knowing what to do, we laid down to watch the buggers, as I called them. I looked at Eugene and his eyes looked like they were ready to pop out of his head. I told him we would try and slip around them and trust to their honor not to bother us.

If we could get to Pensino's house, we would be safe. It was now about four o'clock. We started down the rolling prairie toward them, hoping to see Pensino. When we got down to where they were, I found there was about half of them drunk and the rest of them sober, so there was a sober Indian with each drunk one.

Native Indians were not happy being moved from their lands

One of the drunk men hollowed at me and said, "White man nippanannoah." That is to say, "Water, go bring." They speak their words back-wards. The sober man told us to go on our way and pay no attention to them. I learned that the sober man was to take care of the drunken one to see he was not hurt. The sober man would not touch a drop of the wildfire, as they called it.

We soon got to the wigwam of Pensino and found that he had to flee in order to save his life. Everything in his house was broken up and thrown out the door and torn to pieces.

Pensino's son-in-law came to us and told us not to be alarmed and that Mr. Pensino would be back before long. Shortly, another Indian came up to us. I had gotten acquainted with him and I was on friendly terms with him.

He told us to go and get up into the wagon that Pensino had there and that the Indians would not come near the wagon and would not harm us in the least.

It was getting dark and Pensino's son-in-law hurried off to save himself. We took the Indians advice and got in to the wagon and huddled up together.

The Indians surrounded the wagon, whooping and yelling all the time, but did not come to the wagon. It was now about ten o'clock at night and raining. The Indians started a fire in different places. We did not know what it all meant. We were wet and hungry and did not know if we would escape or not. I was afraid they would tie us to a tree and burn us. We were both scared half to death.

The rain had begun to pour in torrents and it was so dark we could barely see our hands before us. I noticed a figure of a man coming with something in his arms. We were scared thinking that our time had come. My heart was in my mouth as I watched him come closer. Now, I wished we were home.

At last he came up and to my happy surprise it was the Indian who had told us to get in the wagon. He had brought us a couple of blankets saying, "Too bad the white man get so wet, heaps of rain." "We can stand the rain, if we do not get hurt by the red man," we said. "You safe here. No bother you. Me watch them. Now me go."

So saying, he gave us the blankets and disappeared into the darkness. We felt better and put the blankets around our shoulders and settled down for the night.

Planting corn and killing buffalo, new

settlers barely survived a severe winter

in the new territory, Daniel Weaver didn't

At last the dawn of morning broke upon us and we got out of the wagon and looked about. Presently, Nimwis, the name we called our friendly Indian, "Fox" in our language, came to us grinning, for we were as drowned rats. I asked him about Pensino. He said Pensino was hiding out from an Indian who was his enemy and was watching for him from across the creek. He said he might not be back for a week.

This Indians name was Green and was the one who destroyed Pensino's household goods. Pensino lived somewhat like the white man, having furniture and dishes of all kinds. I asked about something to eat. We had not eaten since the morning before all this happened. He said that there was nothing left of any kind.

We started for home, hungry and wet, with the friendly Indian guiding us safely through the campers. We got out of their camp and gave each other the counter sign or goodbye and started for home.

We had twelve miles to go across the prairie. Often we would see an Indian loping across the prairie. We had no road to travel, only the trails made by Indians. We arrived at Mr. Mays, who lived about two miles from home. We decided we could make it on home, so we didn't stop to get food. We hurried on as fast as we could to where Mr. William Crosby lived, our neighbor. He had a small grocery store. We purchased a few crackers and hurried on home.

Upon arriving here we found our sister and mother both sick in bed. We got ourselves something to eat and rested for a while. It was about this time that the Mormons were coming on their way to Salt Lake City, and stopped over between our place and Atchison to rest for a few days.

They had the cholery (cholera) and it was scattered all through the neighborhood. Many other diseases were raging in that section of the country. It was some time before the sick was able to be up. Eugene and I got rested and was able to help with the sick.

Rev. Knox was our minister and he would often come by and visit us. We would go and hear his sermons on Sunday. So, we enjoyed life fairly well, considering the hardships of those times.

But not for long. More and more sickness came into our neighborhood. It was indeed a distressing time. Our neighbor Mr. Crosby, who had the grocery store, took sick and I tended the store until he got up and about.

When I came back from helping Mr. Crosby, a message was waiting for me from Mr. Pensino to come back and work for him. Father said I had better go and see him and get the money he owed me, even if I didn't work for him anymore.

Eugene wanted to go with me, so we went. Father said he would come after us and look over the country and perhaps find a good timber claim. I had told him about the fine timber land I had seen on the creek bottom.

I worked for Mr. Pensino for about three days and took sick. Father came the next day on horseback after us, not knowing I was down sick. He had left the family sick at home.

We finally got home after having to cross creeks that were flooded. Father waded ahead of the horse to guide him so he wouldn't fall down and dump me in the water. The water was up on father's neck in places. We reached home late in the evening of the next day and found the family all sick, not able to help one another.

I had to go to bed also. My brother, William, was the only one able to wait on us. I was fortunate enough to get better in a few days.

My father took sick soon after and was very bad. Not any of them wanted anything to eat. One day father told me to butcher a beef. I did so right away and cooked some for the family. We had no way to keep the meat on hand. I took the remaining three quarters to Atchison to sell. I think there were three men there to buy it, crying out, "Hurrah for Atchison."

This was the first beef sold at that place. Mr. Allen, the storekeeper there came out to help me cut it up. The people called it the great marketplace of the Kansas Territory. I cut meat on a log that had fallen near the bank of the river. The people called the log my meat block, and said that I was the first to sell beef in Atchison, Kansas. They called it my meat market.

When I got home, the family was worse than when I left. I was at a loss to know what to do. I went to our neighbors to get help. I found them all down sick too. I did the best I could to nurse them. I had to be up all through the night and they continued to get worse.

I did not know of any doctor in the territory. I told father and mother I could go over to Mr. Mays and see if he knew of a doctor. It was nine miles across the prairie. They were all sick at Mr. Mays. He told me there was a doctor near Atchison. I hurried back home and went about three quarters of a mile to get water for my family. After giving them a drink of water, I went to Atchison to find the doctor.

Everyplace I stopped along the way, the families were all sick. I found a Dr. Keller and it was after dark when we got back home. The doctor said my family were all very bad, but, my father was the worst.

He didn't give much hope for him. He left some medicine for him and I nursed them best I could. They were all down but me. We had planned to go to the mil1 and get some flour ground before everyone got sick. We didn't make it and now we were about out of flour. We had to cross the river over into Missouri to get our milling done.

I got on my horse and galloped across the prairie to Mr. Mays to see if I could borrow some flour. Luck was with me this time for he had plenty of flour. I got fifty pounds and hurried back home. I fixed something to eat and tried to feed them and give them their medicine.

They all ate a little except father, who could not eat anything. He would not take his medicine. The medicine made them so sick that he could not eat. We had five cows to milk, but I was compelled to turn the calves in with the cows for I did not have time to milk them. So we were without milk and butter.

The doctor came back the next day and said they were all doing fine. He left more medicine and went on to visit other sick folks. He did not know when he would be back. Now a week has passed and they are a little better but awful weak.

The time was for an election which would determine whether Kansas would be admitted as a free state or a slave state. This was a very important election for the settlers of Kansas.

The Kansas voters were holding a convention and the election was only a few days off. This caused a big time among the settlers of the Kansas Territory. The people from Missouri would come and claim to be settlers of Kansas in order to vote to make Kansas a slave state.

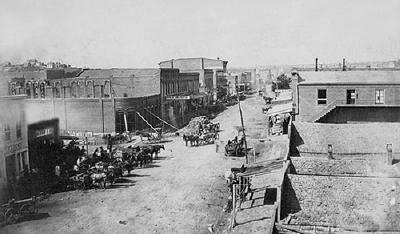

Lewis and Clark came through the area 50 years before the

early settlers came to Atchison in 1854, the town rapidly

grew after the account by Ben Weaver, photo likely about 1860

Atchison photo shortly after 1860, rapidly

growing, Amelia Earhart was born there is 1897

The true settlers of Kansas resolved to defeat them if it was in their power. When the day came for the election, Mr. Mays came after my father in his buggy, but father was not able to go. I had to say home and take care of the sick ones.

The election came off and we gained victory. We could now place our feet on free soil.

A man living to the south of us came up and said that there was a whole family that had died and no one knew anything about it until they were all dead.

They had been dead for several days. I began to wish I had never heard of Kansas. My father, mother, brothers and sisters were all sick and father was getting worse.

He had not eaten for three days. All the medicine the doctor had left was gone and I had nothing to give him. I got some Boneset root and made some tea. It did them no good. I tried some Wahoo (whiskey) and this also did no good. All seemed to be getting worse and I was afraid I would lose them all.

Father turned himself in the bed and motioned for me to come. He asked me to lay my little sister, Adaline, seven years old, beside him so he could see her. He laid all afternoon and watched her. He became much worse by evening and grew steadily worse from then on.

This was Friday night, October 12, 1855.

I told my mother I did not think father would get well. She said, "Good Lord, we are all going to die here and no one will know anything about it until we are all gone."

On Sunday morning Dr. Keller came by. He said father was sinking fast, but that the others were better. Our neighbor, Mr. Knox, came by and stayed until after father died. He died Sunday morning about eleven o'clock on October 14, 1855.

I got Mr. Knox and Mr. Smith to dig the grave for my father. We had to haul him with the ox team ten miles to Atchison. We got within two miles of Atchison and met Mr. Knox and Mr. Smith coming back from digging the grave and they were both so drunk they could scarcely sit on their horses. They said they had dug the grave, just as I told them.

I told them to dig the grave down nine feet and I would pay them for it. The reason for having the grave dug so deep was to keep the wolves and other animals from digging the dead bodies up.

While we were talking it began to rain and it was getting late. It was nearly dark when we got to the graveyard and still raining. We found the grave they claimed to have dug. We were so greatly surprised to see a small hole scarcely large enough to bury a cat, only two feet deep and about a foot wide.

I was at a great loss to know what to do. I went to Mr. Allen who kept the tavern and told him my trouble and got a lantern from him. There were two Irishmen there and I got them to help me dig the grave.

When they got through they had dug it nine feet deep. Then Mr. Snyder and I let father down in the grave and covered him up. It poured the rain all the time and we were soaking wet.

When I got home I found them all about the same as I had left them. The next day I went to Atchison to get medicine and went to doctoring them myself and soon had them all up and getting better. When the family got strong enough to travel, we sold our claim and stock at a very low price and started back home to Barbour County (West Virginia).

We got a German by the name of Myers to take us to Atchison. We stayed there overnight with Mr. Allen. The next day we heard there was a boat coming down the river. Mr. Allen hailed it to stop as it was about to pass on without stopping.

He helped us get on the boat with our belongings and a horse father had given me. Mr. Allen gave me three sacks of corn and a big bundle of hay to feed the horse. He wouldn't charge anything for it.

As the boat was leaving I threw three half-dollars back on the bank to Mr. Allen. He picked it up and bade us farewell. We were on our way home.

We all got seasick. We made beds on the boat with our bedding and all, to lay down on. The fare from Atchison to St. Louis was $77.00. On our way to St. Louis, the boat ran into a snag and tore off the side of the boat, including the cook's cabin.

This caused us days of delay getting repairs to the boat. We got this repaired and started on our way and again snagged a hole in the hull, six inches. We stopped it up with old pieces of clothing and then put three pumps to work to get the water out.

Then at daybreak, the boiler burst. We all rushed to the stern, intending to jump overboard. After examining it, we found about two feet open on top of the boiler. So we kept on going.

We made it to St. Louis and there got another boat. We traveled from St. Louis, Missouri on the Mississippi river to the mouth of the Ohio River. Then on the Ohio River to Parkersburg (West Virginia). We then went up the (Little) Kanawha River to Gilmer County, where my brother lived. John Weaver, my older brother, was married and he did not go out west.

We got robbed on the boat of all our money and mother's trunk. Mother had put part of her money in the trunk and part of it in her stocking, along with the key to the trunk and the weigh bill for her trunk. While she was asleep one night, someone cut her stocking and took everything. She could not claim her trunk because she did not have her weigh bill. So we had nothing left.

We stayed with John (Weaver) for a few days and then went to Barbour County and stayed with my sister, Polly, who had married Edgar Poling.

Eugenous (Eugene) stayed on with John and later married and settled in Gilmer County. We stayed with Polly until we found a place and settled down.

After a few years, I went back to Kansas for a visit. Thirty-five years in fact. Eugenous (Eugene) went with me. It was a thriving farming community. This was the year 1881. We met with old friends who were now prosperous farmers and businessmen. The little town of Atchison had grown to be a big city and my father's grave is now under part of the city.

"Farewell to all my Kansas friends

of whom you can boast;

I often recall the days that are past,

when near my father's host."

"But now he lies neath your city walls of Atchison;

where oft you tread."

"We all must part from off this earth,

and be numbered with the dead." - Benjamin Weaver

A note added years later by Benjamin Weaver: "My Aunt Lucinda Carpenter, daughter of Almira Weaver Carpenter, said that she heard her mother talk about this trip and told that they had to tie their cows and calves to an iron stake to keep them from blowing away in the wind (tornado). The wind did blow one calf away and they never did find it."

"All the families had underground shelters to run into when they saw a storm coming. They had beds and food in the shelter. She also told about the big snakes they had to watch for. The struggle with Cholera and Ague (something like Malaria Fever), together with the fight about slavery gave Kansas the name of Bleeding Kansas."