HUR HERALD'S TALES OF BEAR FORK - Rosedale, Shock, Tanner Creek, Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad

2000

A story of the rise and fall of communities is not uncommon, but the intensity of pulling the natural resources from Braxton, Gilmer and Calhoun County is a grim reminder of what can be left behind, when it is over.

It is difficult to believe what went on during the early part of the last century, particularly when you drive up and down these very roads and trek into the backwoods of Bear Fork.

Here are some more pictures, most of them supplied by Gilmer County historian Ron Miller and his friends:

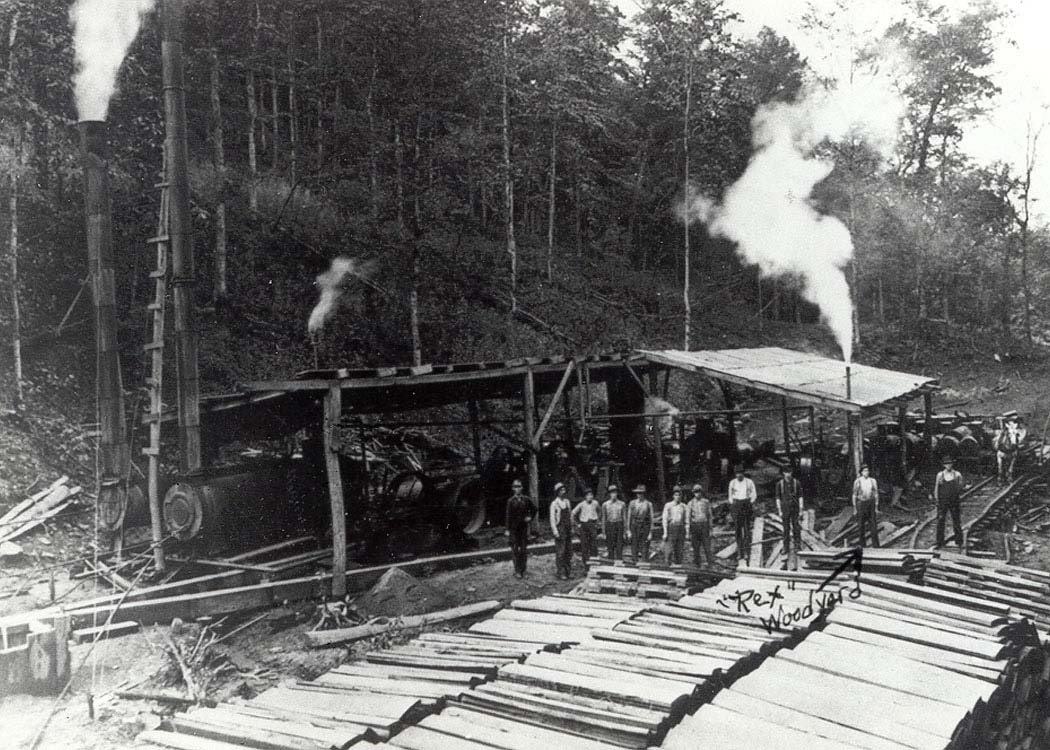

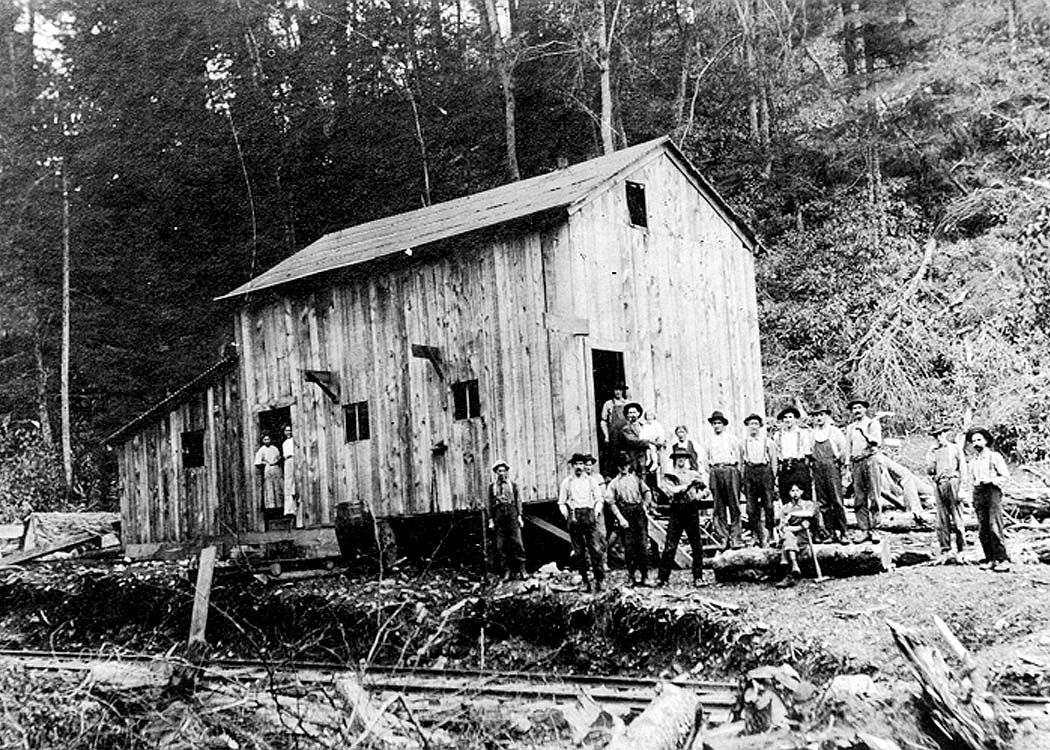

Bear Fork Mill, Rex Woodyard third from right.

Rex was Engineer on Elk & LK Railroad.

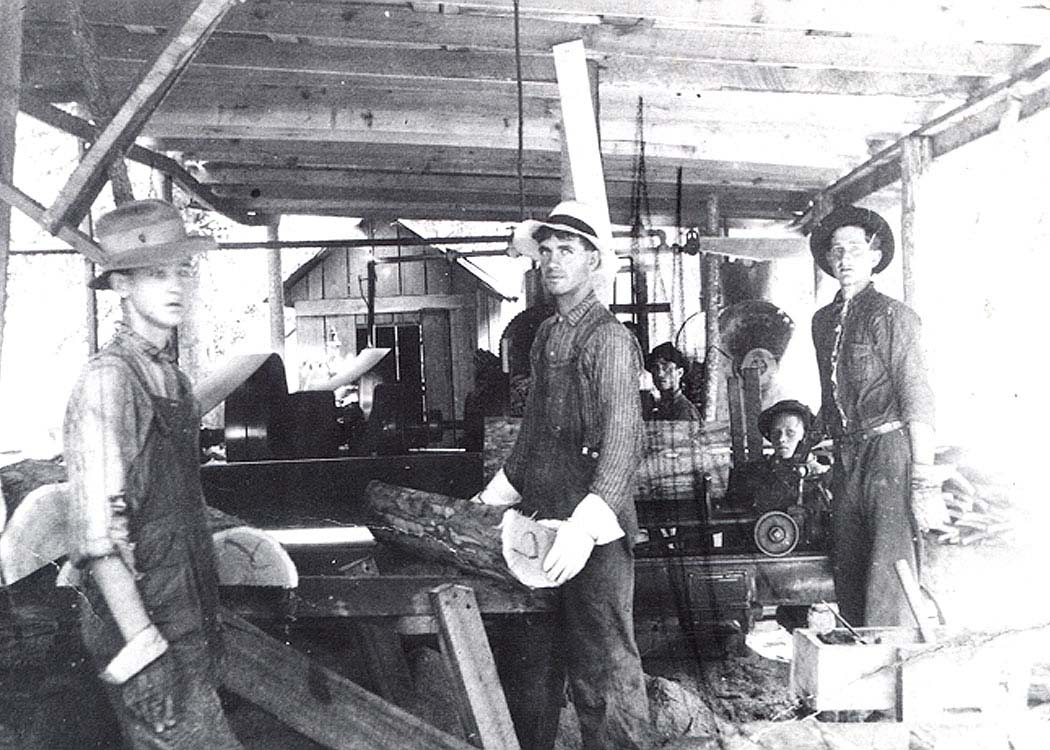

Bear Fork Mill Workers

Tramway used in timbering Bear Fork. Tom Conrad, driver.

Many, Many Ox Teams were needed

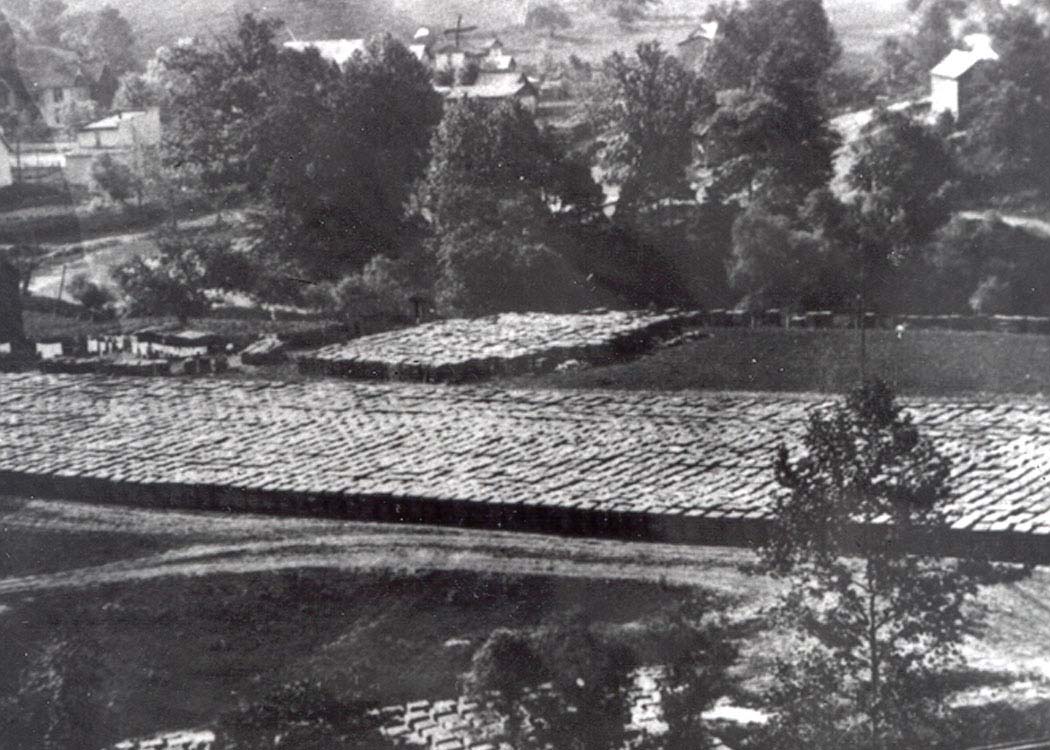

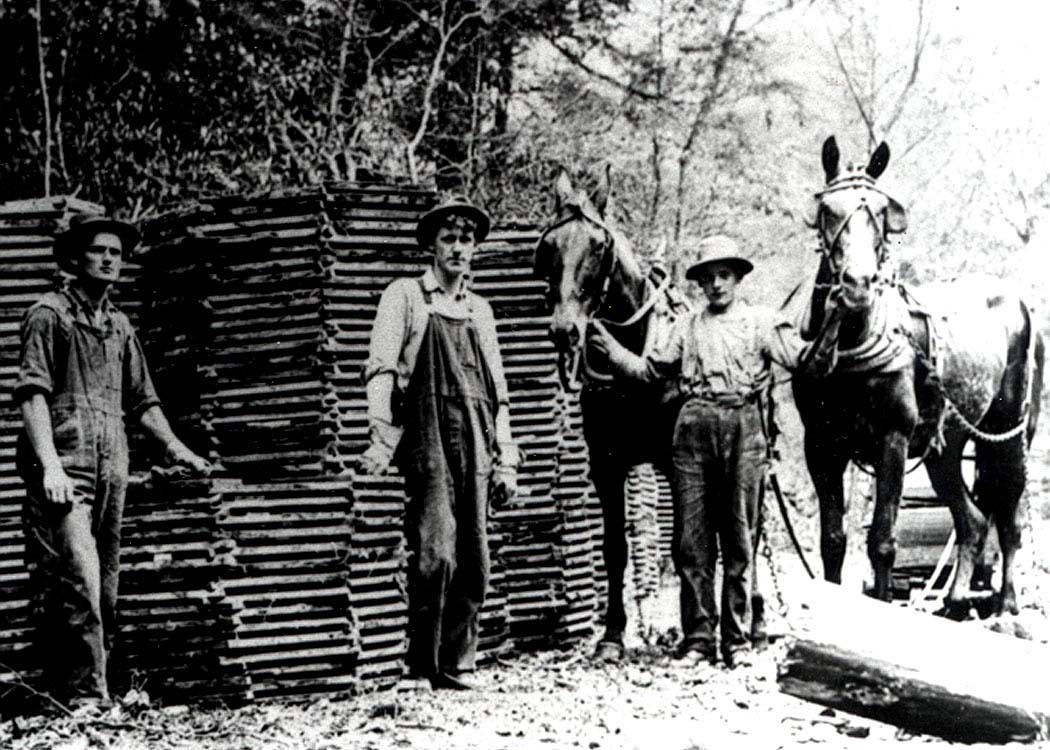

Tens of thousands of barrel staves

out of Bear Fork awaiting shipment

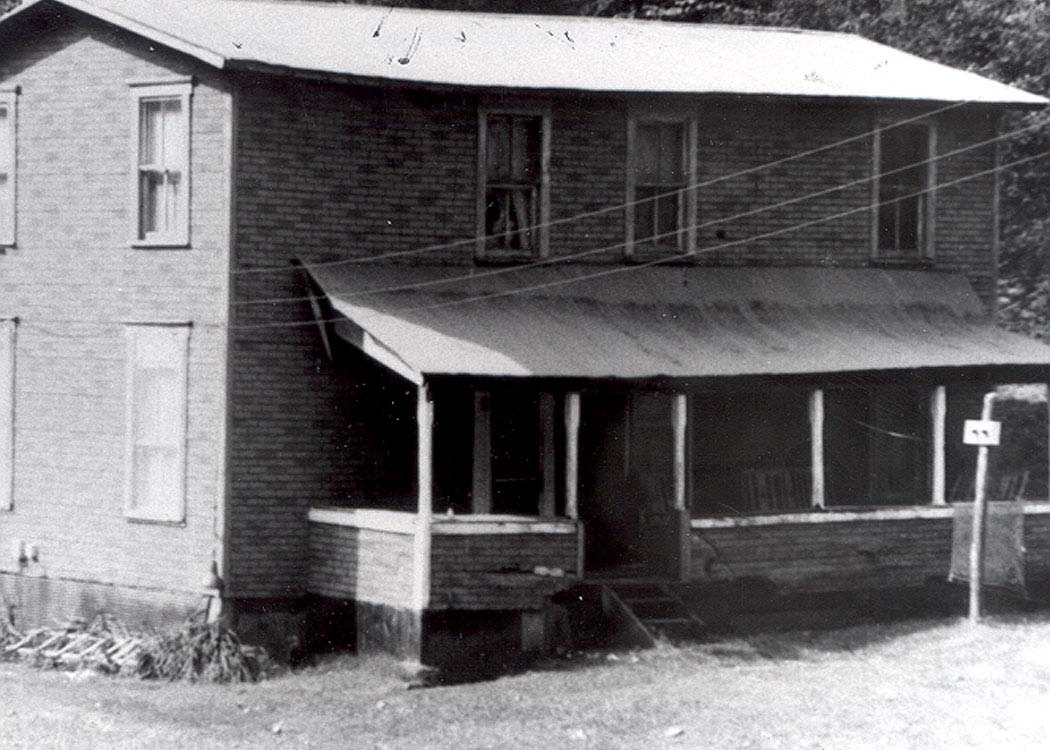

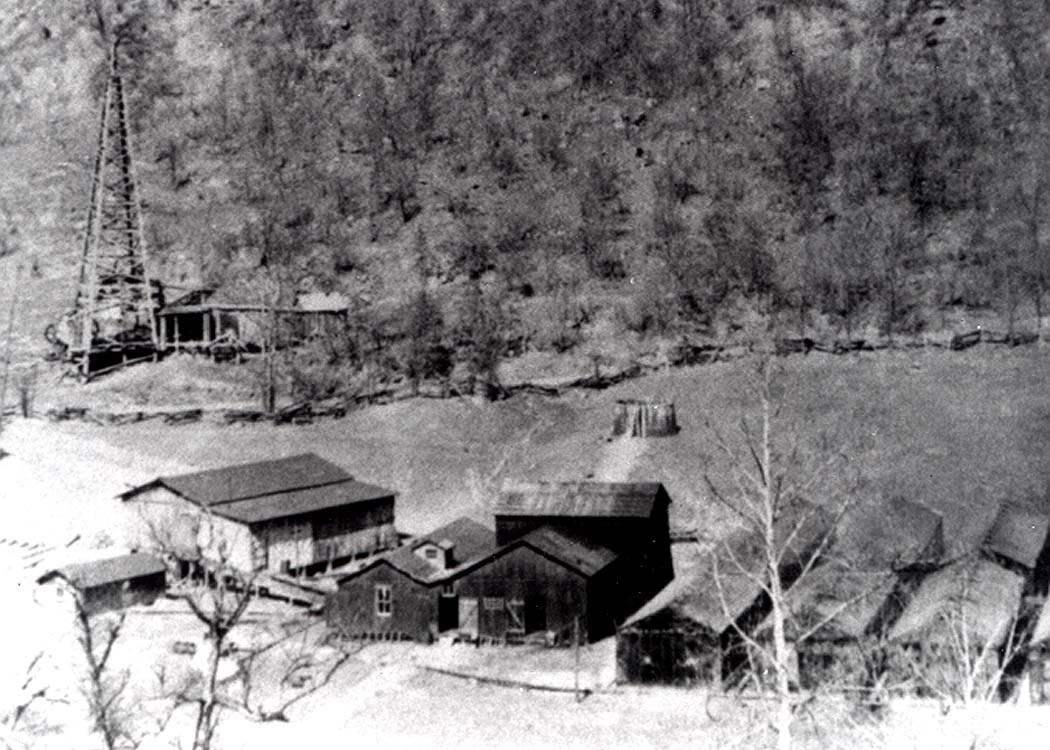

Interstate Cooperage Office at the Mouth of Tanner

Elk and LK Railroad in Bear Fork

Families were proud of their Ox Teams

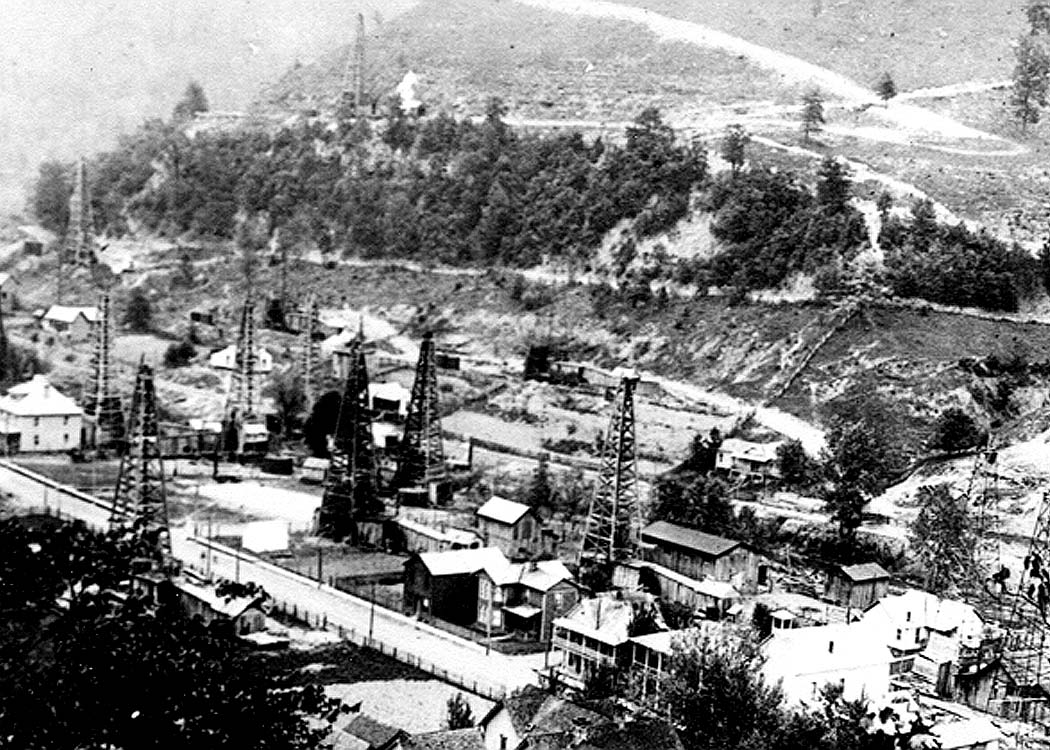

Rosedale - About 1900. Upper end looking down.

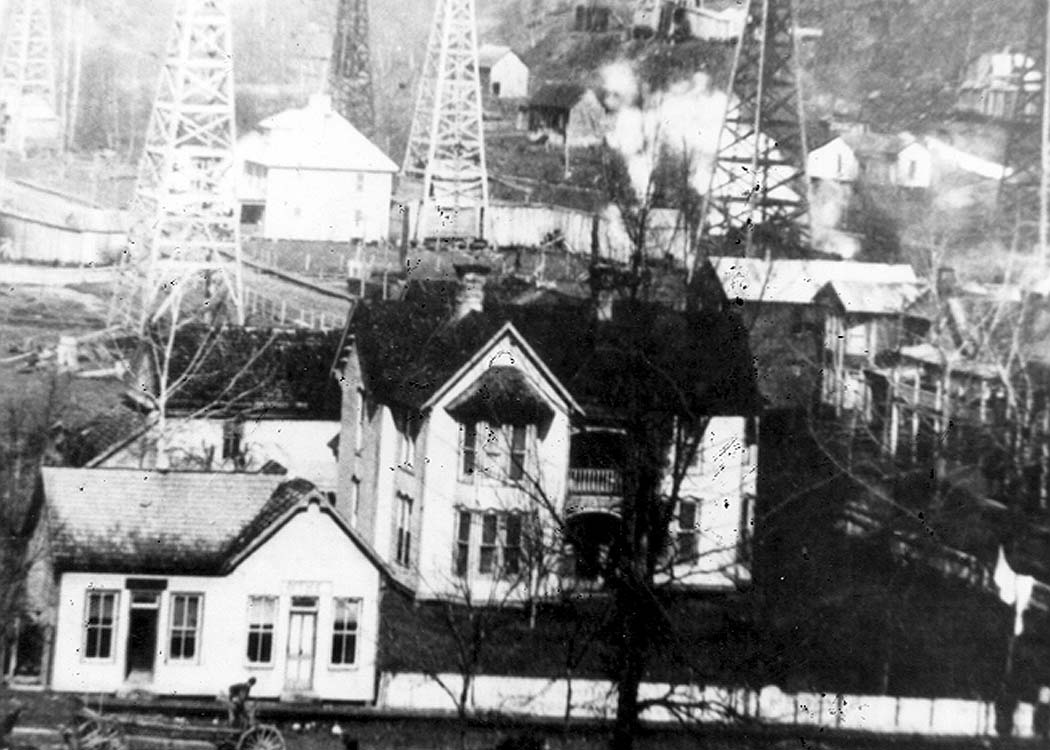

Downtown Rosedale at the turn of the century

Carbon Black Factory between Rosedale and Shock

THE YEARS OF THE ELK AND LITTLE KANAWHA RAILROAD (8/24/00)

By Annie Harvey Dulaney

Braxton County Historical Society Journal - December 1976

In the years 1910 to 1919 my family was living beside a small stream called Big Run which flowed into Elk River at Frametown, about a mile and a half from our home. The family was made up of my gentle hard-working father who was a farmer and a Baptist minister; my slim, dark-haired mother who kept so busy during the day and played her organ in the evening after work was laid by, my grandmother, who died in 1912 at the age of 69; myself; a younger brother; and our baby sister.

My parents, though lacking much in worldly goods, were most generous with their time and talents, not the least of which was helping to care for the sick in our neighborhood with such an occasion arose. It was not easy in those days to get to a hospital, so the sick usually stayed home and were looked after by their own relatives, with the help of good neighbors.

Summers were happy times for us; we raised a garden, picked berries in the pasture fields, gathered summer apples for pies, applesauce, and best of all -- for the large, luscious cobblers my mother made. Not much fancy food was found on our table, but we thrived on mealy boiled potatoes, corn on the cob, sweet potatoes baked in the oven, lima beans, green beans, meat with slices of salt-rising bread or thick squares of cornbread. Quite often others ate with us, for our home was a stopping place for those traveling between Rosedale and Frametown. Friends would come from Rosedale way in the evening, spend the night, walk to Frametown the next morning and catch a train to Elkins or Charleston; then maybe stop on their way back. We always had plenty of company.

As children we fished for minnows in the creek and even had a swimming hole in the orchard through which the creek ran. We brought in the cows of evening, fed the pigs, and gathered the eggs. One late afternoon when I was about six years old, I had gone, basket in hand, for the eggs, and under the roost sat a brown animal looking, as I thought straight at me. I ran to the house screaming, "Grandmother, Grandmother, there's a bear in the hen house!"

Grandmother came, walked to the door, looked inside and said, "That's not a bear -- it's a groundhog. A bear is a big animal." Then seeing I was ashamed for my mistake she added, "But it is a very big groundhog. No wonder you thought it was a bear."

Often we played in the "Lower Woods," a small patch of woodland not far from the house. There we had a grapevine swing and a playhouse. We watched eagerly for the first flowers of spring in wood and field -- trail anemone, wistful bluets, dogwood, daisy, lady slipper, violets -- we loved them all.

Winter, for all its cold and snow, was a good season too. On freezing nights we sat around the fire with a basket of apples or a pan of popcorn close by. One of our parents would read aloud by the light of an oil lamp-- Bible stories, fairy tales, Aesop's Fables, old myths, poetry. Especially did we look forward to the Friday night reading for Friday was the day the National Stockmen and Farmer came with its serial by Louis B. Miller. Miller's frontier tales of early settlers and Indians were enjoyed by the entire family and at the same time were very popular in most rural households. "Fort Blocker Boys" is the story that I remember above all the others. We lived in the lives of its people -- people who endured deprivations and dangers of frontier life, and we felt a kinship with the two boys who were the main characters. One boy was named "Thad," the name of the other is forgotten.

It was in the long winter evenings that I, by dint of much practice, learned to play my first hymn, "Oh, Happy Day." I memorized all the words, too. And, to me, at least, it seemed quite an accomplishment.

Winter evenings were good times for games also, and we spent many happy hours with dominoes, Old Maid, checkers and Authors.

Two playmates of those days are fondly remembered by me. One was Nettie, a little girl my own age. On Sunday morning we went to church with our families, but in the afternoon Sunday School classes were also held in a nearby schoolhouse to which we were permitted to go "all by ourselves." When the time came to start, we set forth clad in our white dresses, shiny patent leather slippers, long white cotton stockings and hats. If it appeared rainy, an umbrella had to be carried; if the sun was shining and the day was hot, an umbrella had to be taken to keep off the sun. So, what ever the weather, almost always, one of us carried my mother's big black cotton umbrella with a silver knob on the handle. Usually Nettie was the carrier for it was her wish, and even in those early years I hated to bother with an umbrella. Nettie's family moved away from our community when she was still a child, and I never saw her again.

The other friend was a small boy on an adjoining farm. He had a first name, of course, but was the youngest of several brothers and sisters who began calling him "Brother" when he was a baby. So, "Brother" he became to everyone until he was old enough to want to be called by his real name. He was a little older than I and a better speller in second grade, but I was the better reader -- or so I thought.

Brother was very knowledgeable about many things; he knew that the bird which made such a mournful cry during a wet time was called a rain crow; he knew how to bend a pin to make a fishhook; how to tie a thread to a June bug so it could be held while it flew; he knew there were not really any fairies, and he had his doubts about Santa Claus, but so far had no positive proof. He knew where to find the first ripe apples in summer and the first chestnuts in the fall. He knew how to make waterwheels and kites and had learned the song "Casey Jones" from beginning to end. Brother was a good playmate for my brother and me, and grew up to be a good young man. In his teens he went away to work, at first to Akron Ohio, then to Charleston. While there he took pneumonia and died in a Charleston hospital when he was nineteen.

It was in the years 1910 to 1913 that the Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad came through our small community and on to its destination at Shock and outlying places. Its terminus was the town of Gassaway, nine miles north of Frametown. In 1903, Henry Gassaway Davis, who owned the Charleston, Clendenin and Sutton Railroad, and wishing to complete the line from Otter to Clay County to Elkins, formed the Gassaway development company. Eleven hundred acres were purchased, including part of tracts owned by J.M. Boggs and a part of the Israel J. Friend farm.

About that time the name of the Charleston, Clendenin, and Sutton Railroad was changed to The Coal and Coke Railroad. The Gassaway was midway between Charleston and Elkins. There were two divisions of the railroad. Since the division toward Elkins had tunnels and hills and required much heavier engines to haul the trains than were needed on the slightly graded road to Charleston, the end of the two divisions was Gassaway. The shops were located in Gassaway also.

The city was laid out in 1904 and in the summer of 1905 building was begun. A bank was built, followed by churches, a grade school, an armory, hotels, a hospital, stores and many residences. The population grew to around 1200.

This, then, was the town that saw the beginning of the Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad. Its depot and roundhouse were built near the mouth of Little Otter Creek and not far from the Little Otter Baptist Church, which had been erected in 1895. The road, a narrow gauge, was being laid to fulfill a need -- that of transporting staves from lumber operations on Steer Creek to the E and LK stave yard at Gassaway. There they would be loaded on the Coal and Coke car for marketing.

In the section of land between Gassaway and Rosedale were large acreages of timber purchased by the Interstate Cooperage Company, a division of the Standard Oil Company. The company had timbering operations going on in a 28,000 acre tract bought from the Bennett heirs and known as the Bennett land. They manufactured oil barrel staves, and transportation to the outside was needed. A railroad seemed the answer.

So in 1910 the Standard Oil Company began a narrow gauge road from Gassaway by Frametown, to Rosedale, thence to Shock in Gilmer County, and on to Bear Fork of Steer Creek. This was the section rich timber and gas and underlaid with Freeport coal.

The Boxleys, contractors, took over the road construction, and a Mr. Boxley came to superintend the work, which was let out to subcontractors. The surveyed road was laid out in sections. The contractors came by train, bringing their labor force, equipment, mules to be used for heavy work, and whatever else was necessary. Camps were set up along the stretches of road to be made. The first camp below Gassaway, of which any account could be found, was at Pigeon and was called Boxley's Camp. Mr. Boxley had brought mostly white workmen and also employed some local labor.

Pigeon, it is said, received its name from the large number of pigeons that came of evenings to roost in the thickly wooded patches of ground near the river. It is said, too, that the last wolf to be sighted in these parts was seen at that place by a family living on the farm over which the animal was prowling. The next camp was at Frametown, on the hill where Mrs. Zella McMorrow and other families now live. It was a Negro camp with a large corral for the mules.

In time this camp moved on and established itself on Big Run in a level field belonging to Ben Meadows. A large tent was set up as a mule stable. Other tents served as shelters to families of colored people, and a long building of planks housed several. This was the camp I can remember, and I even learned the names of some of its residents. Lena and Dolly were two women that lived in the plank house. Lena was tall and thin and always wore a white turban. Dolly was younger and very pretty.

She dressed in long skirts, high button shoes, and brightly colored blouses. The long house was near the road, and the women and I had a speaking acquaintance as I trudged past on my way to and from school. In a tent beside the creek, not far from a big oak tree a couple lived with their little boy, Charleston. Charleston played on the sand, in the water, and under the oak tree. He seemed a lonely little fellow and probably was as he was the only child I ever saw in the camp except for a baby whose mother sometimes sat with it on the long house steps.

The commissary was built at the mouth of a hollow and not far from the country road. The contractor and his family lived in two or three shanties built farthur up the hollow.

One of the first things that was done at the camp site, probably even before the workers came, was to drill a well, as no drinking water was available.

The camp on the Meadows farm was called the Williams Camp. Mr. Williams and his two sons, Percy, accompanied by his young wife, and Sam, had come from Virginia. Percy was the contractor for the grading, and Sam operated the commissary. Their supplies were brought in by train and hauled to the camp in wagons pulled by mules.

A negro named Jim Bagley was stable boss. Often of evenings the workers and their families gathered around a bonfire, talked laughed, and sang the plaintive songs so loved by their race. Passersby and those living near enough the camp could hear the clapping of hands and the blending of voices in "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," "Massa's In The Cold, Cold Ground," "Oh, Mary, Don't You Weep." They also pitched horseshoes and had wrestling matches. On the slope of the hill on which the Big Run Cemetery is located, a negro workman is buried. The story goes that Jim, the stable boss, and a friend were wrestling when the friend fell dead of a heart attack. He was buried and a large, rough stone was placed at the head as a marker. I have often seen the grave, but not of late years, so do not know whether or not the stone has been moved. But, for more than sixty years that neglected resting place of an unknown negro man has been there, a silent reminder of the Williams Camp on Big Run.

The Williamses had charge of the grading of the road from Lower Rock Camp to the top of Big Run Hill, about 4-1/2 miles. Austin Hall, of Frametown, then a lad of thirteen, was water boy for the crew. He carried two large pails, filled from wells of obliging households along the way, and had a tin cup hooked to the handle of each. He had not much time to rest for the sun and hard work caused constant thirst among the workers and kept him moving from one end of the line to the other.

It was a scene the like of which is not known in our county nowadays. Large mules, three abreast, pulled the huge scrapers. The sun beat down, sweat glistened on the faces of the laborers wielding pick and shovel, drivers shouted orders to their mules, clouds of dust rolled up leaving a film on bushes and grass, and through it all came came, from parched throats, the insistent cry, "Water boy, Water boy!" Austin was paid 75 cents a day, a 10 hour day. When school started in the fall, he quit work to attend the Frametown School.

A good bit of blasting was done on this road. Holes were drilled by hand with sledge hammer and steel. A row of holes was made; the fuses were lit by several men, if the line was very long, each man touching with a match perhaps three or four fuses. Then at the yell, "Fire in the hole!" everyone ran for cover. Warder Dean of Gassaway, whose early years were spent on a farm near Herold on Birch River, says that the shots could be clearly heard from his home, a distance of eight or ten miles.

The railroad reached Frametown but affected it hardly at all as it did not go through the main part of town. This community had received its name from a man named Frame who built a water mill there on Elk River about the early part of the first decade in the eighteenth century. Years later, Henry Waggy put up a steam mill with a roller process for making flour.

Frametown, with a population of about 150, had a Methodist Church, millinery shop, blacksmith shop, grist mill, a barber shop, hardware store and coffin shop, a livery stable, a jail ( which later burned), and a two-room school.

The railroad traversed the north side of the Elk from Gassaway to the moth of Big Run and up near its source, but started around to the right before it reached our farm, so it did not pass us directly. At the top of Big Run Hill, a very deep cut was made. A tunnel had been planned but for some reason the idea was given up. On the other side of the cut, the road veered to the left, passing through the Henry Dickey farm, well known for its apples, peaches, and pears, and for a large spring. On it went, past the village of Grose which had mills, a store, several houses, and stacks of staves and boards awaited the coming of a train to provide transportation to market.

Mr. Boxley had this camp. The labor was made up largely of Swedes, Italians, and local men. Grose, and Tague, the next village, were to be stops, but neither ever had a railroad station. At last Rosedale was reached. A depot, one of the three on the line, the others being Gassaway and Shock, was built to the left of the track coming into Rosedale. It was near a two-story house later called the Stewart Wright home and not far from the site of the lamp-black factory.

Rosedale had two one-room schools--one on a hill not far from the Methodist Church, the other just outside the town close the Baptist Church. It had a boarding house or two, a flour mill operated by Peyton Dobbins, a blacksmith shop, and a population of about 180. At one time it was incorporated.

Dr. John W. Smith was a practicing physician in Rosedale when the railroad came. The track passed straight through the family vegetable garden! Dr. Roberts settled in the town, about that time and practiced there for many years. His office has been renovated and is now used as a clinic.

From Rosedale in 1912, the road continued to Shock, a few miles away. Timber companies had come into this area of farms, and no work except as farm hands was available, which paid only about 50 cents a day. Residents were elated over high wages paid by the companies, and many signed up for work. The daily pay was $1.60 for labor, $1.75, sometimes higher, for mill worker, $2.10 for circle sawyer, and $2.90 for mill foreman. All worked a 10-hour day. Foster Norman, fifteen years of age, was water boy for a barking crew at 75 cents per day.

The railroad reached Shock in 1913. Shock had a store with Frank Fisher as owner. He was also postmaster. The Fisher children attended the Shock School, taught in 1915-17 by Leo Skidmore (Archer) of Frametown. She boarded for two years with her aunt and uncle, Ollie and Ned Hopkins. Her last year there, she stayed with the Fisher family closer to the school. On weekends she rode home to Frametown on the narrow gauge.

Some of the residents of Shock at that time were Henry Gumm, office manager; Henry Padgett, the Norman Family, Pete Boggs, Ned Hopkins, a Groves family, Berne Conrad, Newton Boone, and an Ulderich family. Their little daughter, Eva, and the Fisher girls, Nancy and Gertrude, were good friends, and they have kept in contact all these many years.

There were several logging operations and quite a few mills in this area. Accidents happened frequently, and the closest doctor was at Rosedale, five miles away.

Bear Fork Timbering Employed Local Residents

Nearly All Work was "Hard Labor"

One can still see the old office building used in those by-gone days. Another landmark is an old log house on the main road, said to have been built in 1840.

From Shock the railroad had spurs running to various places--Tanner area for one. Another spur of the road was one owned by the Boggs Stave and Lumber company that crossed Elk River at Wire Bridge, or Shadyside, to the Coal and Coke Railroad.

It was sometime in 1912, exact date not known, that train service was begun on the Elk and Little Kanawha. Mrs. Louise Meadows remembers that when she was teaching her first school in 1911, workers were laying steel for the road and were approaching Rosedale. She passed them daily on her way to school. And, in a notebook kept by my father is the following: "Dec. 9, 1912, Monday morning. I left Ivydale on Number 2, came to Frametwon, walked to Lower Sleith, 5 or 6 miles, came to mouth of Sleith in time to get on E and LK passenger train to Frametown; then changed to work train and rode to Lower Rock Camp, walked to J.F. Brady's, then home at 7:30. Very sore throat." At the Bradys' residence, he united in marriage their daughter, Harriet, and Mr. David D. Wayne.

The work train mentioned may have been one of those operated by the Boggs Stave and Lumber Company. They hauled from their Steer Creek mills, crossed the bridge they had built across Elk River at Shadyside, and unloaded. The goods were then loaded on Coal and Coke cars and sent to market. The company had a store at that point managed by J.B. Fisher.

So, the train service came, changing our lives in many ways. In order to get a right of way, it had to be made a public carrier, taking on both passengers and freight, thus we had transportation to Frametown, to Gassaway, and to Rosedale. then, too, the camps showed a life that we had not known before. Negroes, Swedes, Italians and possibly other nationalities came and went away, but before leaving some had become known to us and had spoken with us in broken English, revealing their ways of life. One Swede, a very large man, often stopped at our home to buy eggs (he called them "ecks").

The railway, along with the timbering and millwork, provided good wages for several men during its stay. It brought peddlers, hoboes, and drummers, all following the camps.

The days of the Elk and Little Kanawha narrow gauge slipped by. In our own environment and in the outside world things were happening. Better roads in, some places were being built, conveniences such as telephones and washing machines were in use. The Chapel car, Herald of Hope, brought by Rev. and Mrs. Newton, stopped on a railroad siding at Frametown. A revival was held, and the Baptist Church there was reorganized and named Hope Baptist Church. All charter members of that new organization made in 1916 are now deceased. The last two survivors were Mrs. Maggie Wood and my mother Georgia Harvey.

The flu epidemic of 1918 came and passed leaving many deaths in its wake, and its surviving victims weak and shaken. Our nearest physician, Dr. S.F. Given, of Frametown, was kept busy attending the sick over a large territory.

Airplanes were coming into wider use, and in 1917-18 were first used in warfare. Child labor reforms were being brought about, women were agitating for the right to vote. An new dance, the Tango, was taking hold, and the mighty ship, The Titanic, sank in the chill and lonely waters of the North Atlantic Ocean with a loss of about 1500 lives. The bandit, Pancho Villa, was being hunted among the hills of Mexico. General Pershing and U.S. soldiers were patrolling the border.

And far across the ocean, in a small European country, a man of royal lineage was shot and killed, and the continent was plunged into war. In 1914 we began to hear of atrocities committed upon the innocent, of the starving Armenians, of the over-running of Belgium by the Germans, of the heroism of humble people.

In 1915 the British liner, Lusitania, was torpedoed and sunk by the Germans with 128 Americans aboard. This contributed to the United States entering the war in 1917. We heard of farmorettes, young women who dressed in overalls and worked on farms, thus taking the place of young men who were in Army service. We saw those men in uniform--a close neighbor had three sons in the Army--two olderr sons in Brother's family left about the same time. There were "meatless days" and "wheatless days." It was difficult to find sugar for sale.

The war ended with the Allies victorious on November 11, 1918.

Through all those small local events and world-shaking affairs farther away, the timber was cut, staves were made, and the trains kept chugging away between Gassaway and Shock. But in 1917, the timber operations were completed, and in the year 1918, work began on taking up the track. The railroad had been built for a purpose, had served that purpose, and now was to become a part of the past. Sections of the old railroad grade can be seen today; also, across the Big Run Hill and toward Wilsie (once the lumber camp of Grose), one can see where a high trestle spanned the space from one small hill to another. In 1918 the Gassaway Depot, the roundhouse and part of the track were washed out by a flood.

There was Esta Arnett, roundhouse foreman, at the Gassaway station; Billy Johnson, depot agent; Ivan Beall, George Russell, Bob Garrett, engineers; Bert Otto and Homer Bragg, Brakemen. A Mr. Wilson was the conductor. There were many others whose names could not be remembered by my informants.

Sometime in 1919, Foster Norman arrived in Gassaway after his discharge from the United States Army. He had traveled on the Coal and Coke Railroad, expecting to ride the narrow gauge to his home at Shock. To his surprise, he found its service had been discontinued and that the track had been taken up as far as Rosedale. There was only one thing left to do--send word for someone to meet him with a horse.

The Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad was no more, and henceforth would be only a memory--the memory of that brief and colorful existence which forms a part of the history of Braxton County.