LK Railroad cut stone bridge on right-of-way

below Burning Springs above Rt. 5

Jim Burrows stands on typical road bed still present along LK River

By Bob Weaver March 2004

RAILS AND ROADS ARE HARD TIME COMING

Transportation through and over the mountains of West Virginia is still a problem

that holds backwoods counties hostage to what the greater world calls

progress.

A "modern road" to open up Calhoun and other interior counties between the

interstate highway system has been proposed for years. The Little Kanawha

Parkway ideal was launched in the 1970s and the re-emerging Blue-Gray Trail

Highway started in the 1960s. Neither have crossed the political threshold of

likelihood.

The Parkway would connect I-77 at Mineral Wells and I-79 at Burnsville, cutting

through Wood, Wirt, Calhoun, Gilmer and Braxton counties. The Blue-Gray

highway has had several different lives and proposed routes, but would

essentially link Jackson, Roane, Gilmer and Lewis counties parallel to U. S.

33.

When the north-south I-79 was proposed through the state, frequent maps

displayed a straight shot through Calhoun. Local politicos were lukewarm at the

idea, with newspaper editorials saying it was "important to support your local

merchants" and keep business at home.

I-79 was not built through Calhoun, and business still did not stay at home.

There once was promise of a railroad to open the area, but unlike the persevering little engine that said

"Puff, puff! Chug, Chug! Choo, Choo! I think I can, I think I can," the railroad didn't make it up the Little Kanawha

Valley.

A railroad put Spencer on the map.

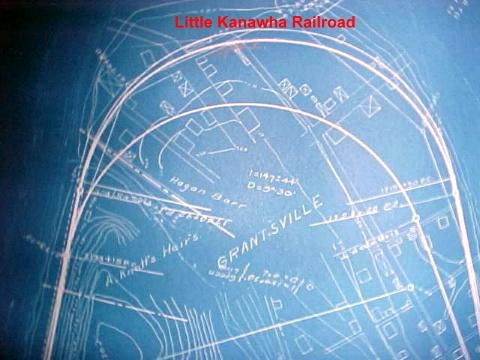

1902 map shows three routes surveyed through Grantsville with route close to River-Mill Street selected (Map from Doyle Hupp Jr.)

Part of roadbed was on what is current River Street, Grantsville

Track would have crossed Grantsville's Simon's Run near this Gilmer-Ritchie Turnpike Bridge, headed upstream toward Glenville

Just over one hundred years ago the opening of the area to commerce was the

visionary Little Kanawha River Railroad. The idea burned bright for a few years,

linking Parkersburg to the mainlines in Braxton County.

The project got underway in 1895 with the purchase of dozens of rights-of-way

from property holders along the Little Kanawha River from the Wirt County line to

the Gilmer County line.

Although the railroad did reach Owensport near Palestine, grading, filling, bridge

and trestle building continued up the river through Calhoun for several years, but

no track was ever laid.

The project took on several different names through several different

companies.

Voters in three Calhoun districts, Sherman, Sheridan and Center supported the

idea when a levy was placed on the ballot, raising $24,000 toward the project.

Riverboat operators and ox-team owners, some owned by county political

families were not so enthusiastic, nor was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The LK railroad had proposed and selected routes, denoted in detailed maps

issued in 1902.

Remnants still remain of track bed where Big Bend church now resides

Survey through "downtown" Big Bend (Brooksville) in 1902 (Map from

Doyle Hupp Jr.)

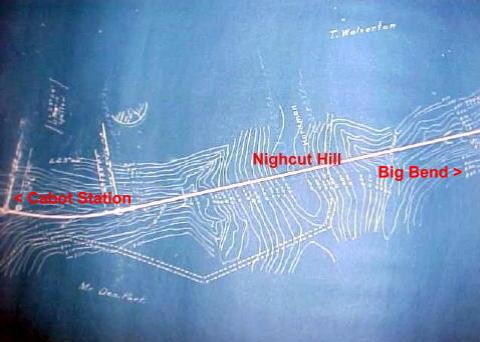

Rail line took a shortcut over Nighcut Hill away from LK River, a steep grade to Cabot Station (Map from Doyle Hupp Jr.)

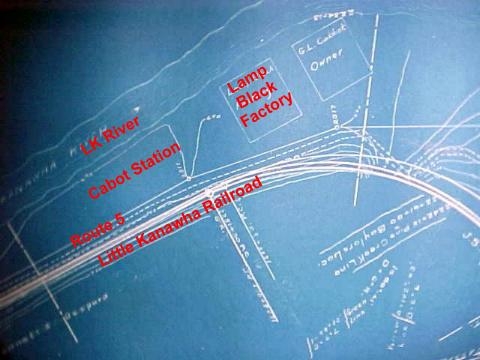

Road was across or on current Rt. 5 at Cabot Station's lamp factory

(Map from Doyle Hupp Jr.)

County Surveyor Doyle Hupp, Jr. said "While the right-of-way cut through the hills

along the river above Creston with at least one bridge crossing, most of the

right-of-way was parallel Route 5."

There are still signs of the early grades along the river and Route 5 at Big Bend,

near the mouth of Big Root where the railroad was to take a short cut over

Nighcut Hill and in Grantsville, near what is now River Street.

Remnants of a right-of-way and bridge building are still visible on the Gainer farm

above Grantsville with stonework for a crossing.

Arling Stutler, brother of historian Boyd Stytler, wrote in the 1960s that the nearest the railroad got to Grantsville was Hamilton Hollow below town, with large amounts of dirt being moved for the grade.

There was a railroad work camp at the mouth of Leafbank with lots of "Negro workers and mules," he said, with another camp near the mouth of Big Root.

"My brother (Boyd) worked at the commissary as a clerk and later he was a water boy," he said, recalling a large number of Italians had worked on the project "baking their own bread."

Much of the grading has been disrupted by the building of houses, roads and

other projects.

Farmer and businessman Francis Cain, who lives above Big Bend along the river,

said the railroad company purchased rights-of-way with and without reversion

clauses. "During the 30s a lot of people got upset because the railroad

rights-of-way were stuck," in legal limbo, the company having gone bankrupt.

The Little Kanawha Railroad encountered financial trouble, and began to sell-off

its interests to other companies after it was placed in receivership.

A new company launched a project that called for the construction of six tunnels

and nine bridges between Parkersburg and Grantsville. Construction began in full

in 1903 with grading and building trestles. Once again the project ran into

financial problems when the railroad canceled its plans in Gilmer County.

Blaming began, and the Grantsville Town Council offered to

assist the project in any way they could. A citizens meeting in Grantsville in 1903

called for completion of the project.

Calhoun residents blamed each other for the failure of the project, but accounts

said the county had little control over the ill-fated project.

Charges arose that money was stolen from the $5,000,000 project, and a

congressional investigation was launched several years later.

A railroad effort that did materialize in parts of Calhoun shortly after 1900 was the

Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad, which came from the Elk River at Gassaway

through Rosedale and Shock to run deep into the primitive Bear Fork. (At least

eleven articles and dozens of railroad pictures from Bear Fork can be found under

People, Humor and History: "Tales of Bear Fork").

The E & LK was a narrow gauge which ran into Calhoun County at least eight

miles, both down the right fork of Crummies Creek and down Frozen Run and a

short distance up Nicut. It also had a terminus along US 33-119 at Steer Creek,

with the ill-fated intention of connecting with a "main line" at Russett.

Winding its way through the backwoods, the Standard Oil financed the train to

haul tens of thousands of logs and barrel staves from the sawmills.

Read Part Two: Millions Lost In LK Railroad Collapse

|